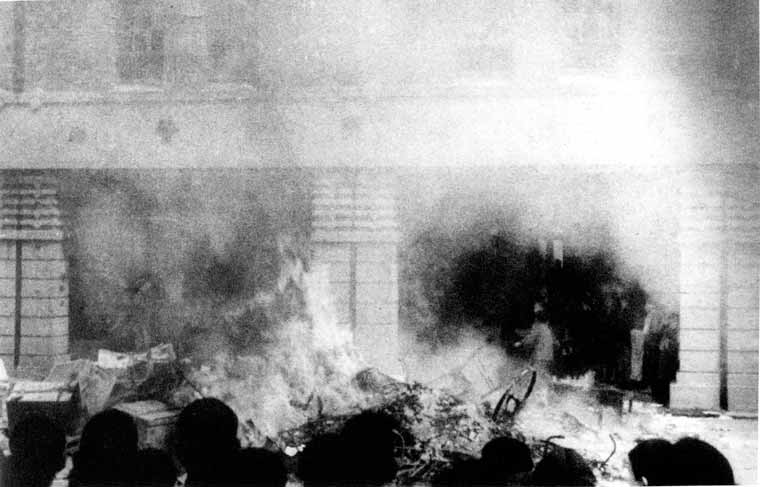

Yidingmu Police Station, Taipei, the morning of February 28, 1947. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A Metropolis of Unhappiness (1989) was digitally restored and rereleased in theaters throughout Taiwan earlier this 12 months. Working two hours and thirty-seven minutes, the melancholic art-house movie exhibits in painstaking element the dissolution of a Taiwanese household prompted by political regime change following World Battle II. In 1945, the Japanese surrendered Taiwan; quickly after, Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang celebration (KMT) would retreat from China to the island, violently suppress native uprisings, and formally declare the island as its personal in 1949.

“This island is so pitiful. First the Japanese after which the Chinese language. All of them rule us however none maintain us,” one of many movie’s protagonists says in Taiwanese, a language that the KMT banned from faculties. The English subtitles have been much less refined: “All of them exploit us and nobody offers a rattling.”

I attended a sold-out exhibiting on opening weekend. In a considerably surreal coincidence, the rerelease date coincided with the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Simply hours earlier than I noticed the movie, I’d biked to a public sq. the place a crowd of principally Taiwanese folks waved Ukraine’s blue-yellow striped flag. When Ukraine’s anthem was performed, everybody put their arms on their hearts. One Ukrainian mom mentioned to me, “Taiwanese folks know what it’s prefer to have a loopy neighbor.”

As we speak China claims it should take Taiwan by power; the specter of regime change is rarely far. In Hong Kong, the place the movie was additionally rereleased this 12 months, protesters, amongst them excessive schoolers, have been imprisoned and sentenced for subversion. However to be honest, in Taiwan—a rustic dominated by six successive colonial powers—it might be tough to discover a launch date that didn’t tackle a deep sense of resonance and foreboding. The 12 months Metropolis was launched, 1989, the Chinese language Communist Social gathering killed 1000’s of nonviolent protesters in Tiananmen Sq.. In distinction, Taiwan was on the cusp of freedom. It burst with nationwide awakening. Quickly, activists who learn Mandela in jail could be launched and run for election—and win.

Metropolis was the primary movie in Taiwan to symbolize the occasions of two/28—a sequence of numbers identified to each Taiwanese particular person at this time, although for many years it might barely be whispered. On February 27, 1947, a state agent beat a Taiwanese girl promoting contraband cigarettes. When a crowd shaped to defend her, a policeman fired into it, killing a person. Individuals throughout the island started to revolt on the twenty-eighth, and within the days following, an estimated eighteen to twenty-eight thousand folks have been killed by the KMT. For practically 4 many years, in a interval now often called the White Terror, Taiwan could be dominated by a one-party dictatorship—the second longest time any nation has been subjected to uninterrupted martial legislation. (Syria has just lately surpassed Taiwan.)

Within the years following Metropolis’s launch, Taiwan has turn out to be a democracy. It’s thought of the freest nation in Asia and among the many freest on the planet. Simply this week Freedom Home launched a report measuring folks’s entry to political rights and civil liberties. Taiwan is ranked sixth on the planet, above each France and the USA. China is listed among the many backside ten nations. Whereas “6/4” is scrubbed from the web in China—even the candle and ribbon emojis disappear from the accessible pool on telephones and computer systems on June 4—the Taiwanese authorities has made 2/28 a nationwide vacation. Schoolkids get that break day.

Metropolis views the trauma of regime change by means of the tales of two fictional Taiwanese households. Within the first, the oldest of 4 sons leads an area gang whose territory is stolen by mainland Chinese language rivals. In the beginning of the movie, he wonders on the misfortune that has befallen his brothers—one has turn out to be a lunatic, one other went lacking within the Philippines whereas serving as a conflict medic for Japan, and the youngest is deaf. “Perhaps my mom’s grave will not be in the appropriate spot,” he muses in Taiwanese.

The opposite household is a brother–sister pair, Hiroe and Hiromi; even their names nod to their cultural affinity with the now-ousted Japanese. Hiromi is a nurse; Hiroe is an intellectual-revolutionary with Marx on his bookshelf. He’d lobbied for Taiwanese rights beneath Japanese colonialism and, beneath his new anticommunist Chinese language overlords, ramps up his activism.

The intersection of those households, and the center of the movie, is the tender love between Hiromi (performed by Xin Shufen), whose diary offers the voice-over, and the deaf-mute photographer Lin Wen-ching (a strapping younger Tony Leung), the youngest of the 4 sons. Lin’s deafness actually and metaphorically displays the silence enforced by the KMT. Lin meets Hiromi by means of Hiroe, who’s his finest good friend. The younger couple sends cash to help Hiroe’s dissident work. By the top of the movie—it’s implied however by no means proven—each males are executed by the regime. Hiromi will elevate her and Lin’s little one alone.

In Metropolis, scenes unfold in Shanghainese, Taiwanese, Japanese, Mandarin—undermining the official narrative of a single nationwide language. For that cause, too, diary entries, songs, notes, and numerous legends permeate the movie. Like currents flowing towards the tide, these are counterforces to the language of heads of state—what Orwell known as the enemy of sincerity.

For survivors of state violence, Hou suggests, there are few sources, little data, and infrequently solely official lies. In a single scene, a lady and her three youngsters obtain a chunk of fabric from Wen-ching, who has simply been launched from jail on expenses of collaboration towards the regime. We don’t know who this girl is; she seems simply this as soon as. We see a close-up of her face and, much less clearly, her youngsters standing behind her as she unfurls the fabric, sobbing when she reads the next phrases, written in dried blood:

LIVE WITH DIGNITY,

YOUR FATHER IS INNOCENT

Who wrote this? Why was their father arrested? Was he executed? On every of those questions, Hou leaves us in the dead of night, although I imagine he does so to make some extent in regards to the confounding, fragmenting power of state violence. Inside this void the fabric tells the reality.

Hou is within the personal pains of upheaval. Prisoners write poems earlier than they die. Hiromi writes in her diary. Wen-ching writes notes. The 2 lovers write to one another, having no different option to talk. These texts seem in massive block print that occupy the whole display in a manner that recollects outdated silent movies.

Why a lot textual content? The movie’s screenwriters, Hou, Chu T’ien-wen, and Wu Nien-jen, have been born after the violent uprisings and grew up throughout a time when it was forbidden to speak about them. To put in writing Metropolis, they sifted by means of diaries, letters, and personal archives. The movie thus stands as a mirrored image on what remembering appears like: sifting by means of textual content. That exercise is soundless. You need to think about the lives of people that have dared to go away a hint.

Contemplate, in distinction, the straightforward but poignant narratives of the White Terror which have emerged within the mainstream information since authorities archives opened within the early 2000s. The BBC reported one such story. “My most beloved Chun-lan,” a father wrote on the night time earlier than he was executed, to his five-month-old daughter, “I used to be arrested whenever you have been nonetheless in your mom’s womb. Father and little one can’t meet. Alas, there’s nothing extra tragic than this on the planet.” He wrote that in 1953. The federal government confiscated it and by no means delivered to his household. His daughter would obtain it fifty-six years later, at age fifty-six. She cried when she learn it. “I lastly had a reference to my father,” she instructed BBC. “I spotted not solely do I’ve a father, however this father beloved me very a lot.”

Narratives like these have a starting (arrest, execution), center (extended, multidecade separation between father and little one; suspended questioning), and finish (cathartic reception of the letter; connection established). One of many central precepts of trauma therapeutic holds that we reclaim occasions of loss by means of narrative. Hou refuses a story, thus refusing reclamation, suspending us within the psychic trauma of his technology.

Because of this, maybe, in Hou’s movies we don’t at all times notice when a scene has ended. One second which I like most is sensual and harmless: Wen-ching and Hiromi sit shut collectively on the ground, taking a look at one another, delighted and stuffed with longing: two shy, delicate folks discovering their option to love. Within the background, the old-timey German lied “Lorelei” performs on a phonograph. Steps away, their male pals sit round a desk, consuming zongzi (a sticky rice dish eaten in the summertime). They complain bitterly of the bribery and corruption that marked and adopted 2/28, which has included nepotism; the KMT has fired locals—calling them slaves to the Japanese—and awarded these coveted authorities positions to relations.

However the two beautiful younger lovers are in their very own world, speaking in regards to the music. Hiromi explains to Wen-ching—in a letter, written in her pocket book—the legend of Lorelei. He writes again, telling her he knew the music earlier than grew to become deaf, then recounts the way it occurred. He was eight when he fell from a tree. A cheerful child who lived in his personal world, he at first didn’t even notice he had misplaced his listening to; his father needed to inform him by writing it down. Hiromi seems stunned, and the digicam cuts to a flashback, a baby imitating a Beijing opera singer. This nearly montage-like scene has no argument, no dramatic rigidity, no climax. It’s all personal logic. The impact is such that even the current second of rapturous love has the texture of reminiscence, recovered too late, ineffective but nonetheless dazzlingly vivid.

***

When Metropolis was first launched, an estimated 50 % of the nation’s inhabitants flocked to theaters to see it, ensuing within the inconceivable box-office upset of a kung fu film starring Jackie Chan. Early worldwide approval for A Metropolis of Unhappiness included the Venice Movie Pageant’s Golden Lion Prize: Metropolis was the primary Chinese language-language movie to obtain this honor. (In September, Tony Leung acquired a lifetime achievement award at Venice, the place three of his movies have received the Golden Lion, Metropolis being his first.) In the meantime, in China, Metropolis was banned till 2012, when it acquired a small exhibiting at a movie institute in Beijing. This 12 months, the digital restoration was proven at movie festivals and in Beijing and Shanghai, marking the primary time that ticket-buying audiences might see the movie. The few showings accessible have been instantly bought out.

But, regardless of Metropolis’s canonical standing in Taiwan, home crucial reception was, and continues to be, uneven. Critics have argued that Metropolis fails to point out the size or barbarity of the killings of two/28. It doesn’t present, as an illustration, how lots of Taiwanese folks on the streets have been bundled into burlap sacks and tossed into the harbor. It doesn’t present unusual residents getting stabbed by Chinese language troopers. It doesn’t present the Butcher of Kaohsiung, as he was named, a Chinese language normal who sprayed machine-gun fireplace right into a crowd. When Hou does present avenue violence, it’s enacted by native gangs and never by the KMT authorities: a band of vengeful Taiwanese randomly beat up folks whereas shouting “Loss of life to mainlanders!” It is a reference to the 2 million migrants from China to Taiwan after 1945, a few of whom confronted discrimination.

Have been critics proper? Partially. For me, the harshest factor I can say about A Metropolis of Unhappiness can also be probably the most unfair: it’s no The Battle of Algiers, a movie that confronted with lucidity the totalizing character of violence. Violence cleanses: that’s the ideology of its perpetrators, from the brokers of the state to rebel terrorists. Like Metropolis, Battle handled colonial occupation; like Metropolis, Battle handled its personal nation’s watershed second of the 20th century. However Battle, which premiered twenty-three years at Venice earlier than Metropolis, uncovered with complexity the levers of energy, portraying a French normal and his rationale for torture with care. In distinction, you received’t discover in Metropolis something about Chiang Kai-shek, who famously mentioned, “I’d relatively kill 100 harmless folks than let one communist escape.” The identify of his marketing campaign in China to exterminate leftists fairly actually interprets to “cleaning social motion.” Neither Chiang nor any high-ranking Chinese language soldier seems within the movie, a lot much less articulates his technique or beliefs; once in a while, a policeman or soldier rounds up dissidents or hauls somebody off to get executed. In Metropolis, the human origins of energy seem shadowy, opaque, with out substance.

In Hou’s protection, Metropolis would by no means have been launched had it featured a Chinese language normal describing a program of cleaning and torture. Moreover, Hou’s model is elliptical and oblique—which additionally occurs to be helpful to evade censorship. “Nothing is worse than having one thing there for the sake of exposition or clarification,” he has mentioned.

What, then, are the politics of the movie? Above all, I feel, Hou describes the inherent price of preserving a free thoughts amid totalitarian situations. Although most of the ladies in Metropolis are seen performing conventional roles—making ready greens within the kitchen, elevating youngsters—Hiromi’s diary offers the story of her internal life in addition to the written narration of her household’s story. The seasons change, from winter to summer season to winter once more, however she retains writing. Equally, regardless of Wen-ching’s incapacity to talk and listen to, he by no means stops observing his environment. The quiet takes wherein we watch Wen-ching creating photographs is a metacommentary on the persistence required to witness the world with open eyes. For these two idealists, the thoughts triumphs despite bodily and social obstacles.

In addition they each proceed to contribute to Hiroe’s doomed resistance motion. Three quarters into the movie, Hiroe escapes jail and creates a little bit socialist utopia within the hills. When he’s not harvesting rice—trousers rolled up, stepping gingerly behind a water buffalo plowing a rice paddy—he’s writing pamphlets. These will spell his demise when he’s finally situated, arrested, and executed by the KMT. However for now he has created a free world. When Wen-ching visits, he replies, “In jail I vowed to stay for pals who’ve died.” A number of beats later: “The one factor that issues is your beliefs.”

Michelle Kuo is a author and professor based mostly in Taipei. She teaches at Nationwide Chengchi College, and her e book Studying with Patrick was the runner-up for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize.