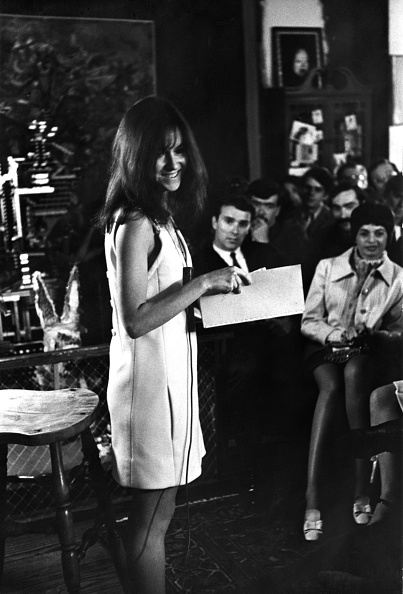

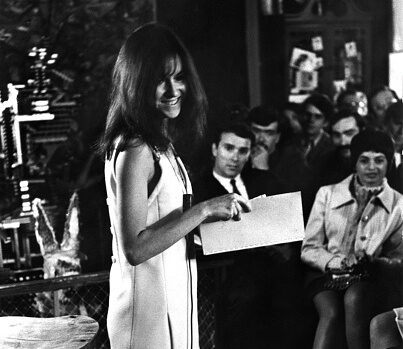

LOUISE GLUCK SMILES AS SHE READS HER WORK TO AN AUDIENCE IN THE HOME OF NORMAN MAILER, NEW YORK, NEW YORK, MAY 24, 1968. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRED W. MCDARRAH/MUUS COLLECTION, VIA GETTY IMAGES.)

Earlier than I can suppose how one can start, she rebukes me: “Regarding loss of life, one may observe / that these with authority to talk stay silent …” (“Bats,” A Village Life).

Flip the pages, to “Lament,” in Ararat, and as soon as extra, a reproof:

Out of the blue, after you die, these pals

who by no means agreed about something

agree about your character.

They’re like a houseful of singers rehearsing

the identical rating:

you have been simply, you have been form, you lived a lucky life.

No concord. No counterpoint. Besides

they’re not performers;

actual tears are shed.Fortunately, you’re useless; in any other case

you’d be overcome with revulsion.

These two strains—a joke that hinges on being useless—make me smile. A reflex, as I’m additionally crying. And I feel, as I usually have, that Louise Glück wasn’t given sufficient credit score for being a humorous poet. She is extra generally characterised as an investigator of loss of life. Some discover her poetry too skewed towards the grave; I’m wondering if we’re too afraid of the truth that breath is the one factor conserving us out of it. To talk of her as if her loss of life is the fruits of the work, although, is to disregard her consideration to loss of life’s huge and fecund reverse, rife with pleasure, with struggling, dominated by silence although it produces a lot speech in defiance: dwelling, within the current steady. To reside is the verb it’s straightforward to neglect you all the time embody. I stand. I stroll round my bed room. I fear the cuff of my grey wool sweater. I contact the petal of an Easter lily that opened simply this morning. I do not forget that Louise prized completeness and element when it got here to pure issues, so I stroll again to my desk. On my laptop computer, I search the Latin title, Lilium longiflorum. I smile once more: my futile try to attract nearer to her turns into a joke that hinges on loss of life.

Again to the e-book. My previous self has drawn a line in blue ink beside this stanza: “Loss of life can not hurt me / greater than you have got harmed me, / my beloved life” (“October,” Averno). Is there the rest to say?

***

My first dialog with Louise was a complete failure. We each thought so.

You need to perceive that I used to be in some important means a feral creature, with that skittish hideaway intuition that comes from working towards survival. Although technically “homeschooled,” I used to be mainly an autodidact: I’d spent years studying my means by way of the library. Since early childhood, my father had terrified and overwhelmed me. When, a bit older, I began to withstand his management, he additionally disadvantaged me of language, conserving me in my room for days with out books. He learn my journals and punished me for my ideas. At 9, I’d began thinning myself compulsively. Then not simply consuming however speaking turned so tough that I usually couldn’t reply direct questions. By twelve, I not often spoke. My adolescence was silence, secret-keeping, determined eager for a special future with out the flexibility to think about any future however loss of life, which I anticipated would come to me younger. You possibly can see why I beloved Louise’s poetry.

When she referred to as me, I used to be eighteen, and had simply been admitted to Yale, the place she taught from 2004 till her loss of life. I used to be at a gasoline station in Lancaster, Ohio, as removed from poetry as wherever may very well be. An unknown quantity, Cambridge space code. The admissions workplace, she mentioned, had despatched her the poems I’d submitted with my software and requested her to speak to me. Neither of us, luckily, ever remembered precisely what was mentioned, however my terror of speaking, and speaking to her, particularly, made me even much less articulate than regular, and she or he, awkward within the face of awkwardness, faltered. “I believed you hated me,” she informed me later. After I utilized to her workshop at the start of my first semester of freshman 12 months, I hoped she wouldn’t bear in mind me. She did. I turned her scholar.

She fascinated me. Her capacity to extemporize in complete paragraphs. Her delphic certainty, a said choice for the particular article, alongside an virtually spiritual dedication to doubt, her sentences chained collectively by small temperings: “a type of,” “as if,” “it might be that,” “I feel,” “I consider.” After which—bang—a proclamation I’ll bear in mind until I, too, now not have reminiscence. Throughout workplace hours, I glanced on the labels of her garments, which fell in luxurious folds of silk and wool and cotton and leather-based, black or grey or a darkish inexperienced, and memorized the names of designers I appeared up later. And I studied her cell face whereas she learn a poem: in these shifting expressions, a theater of notion and judgment earlier than the lifted hand introduced down the pen.

Typically, when she checked out me with a cool hypothesis or, different instances, with a softness I named to myself as pity however didn’t resent as a result of it appeared the mild hand one skilled sufferer provides one other, I felt as if I have been watching her describe one thing to herself, the one thing being me, and generally she did describe me to myself, her readability having a number of the heartlessness of an actual oracle: “You’re keen on your mom and hate your father, and also you hate that your mom nonetheless loves your father.” The depth of my need to be seen matched the depth of her seeing. She acknowledged my docility as a facade (obedience, by no means a high quality she revered), and stoked the hearth that burned it up. No less than on the web page, speech, choked by my father after which on my own, surged forth at her invitation—no, her urging—to talk.

“You will have the makings of an actual poet,” she informed me that semester. Excited, as if she had made a uncommon discovery. I couldn’t meet her gaze; the concept overwhelmed me. Nevertheless it took root in my thoughts and, shyly, slowly flowered right into a dream after which a pursuit. She usually thought in oppositions: “actual” pointed to its adverse, “false,” which was a betrayal of the artwork. (In the identical means, she usually described a poem or a line as “alive,” and although I don’t bear in mind her ever saying one thing was “useless,” I heard the unstated downside.) “‘Poet,’” she wrote in an essay about her personal training, “have to be used cautiously; it names an aspiration, not an occupation. In different phrases: not a noun for a passport.” In her encouragement there was a warning, and a goad: You will need to do the making, Elisa, and the making goes on until you finish.

She rejected a lot of my strains (“inert,” “hopelessly typical”) however she by no means rejected my ideas, irrespective of how merciless or deviant or unusual. Typically she anticipated the logic or the emotion, as if it have been pure, a minimum of understandable. In entrance of her, to her, for the primary time in my life I may say something.

***

The primary time I learn Louise’s poetry, I used to be twelve and sitting on a concrete berm at a gasoline station in northern Ohio. Close by, my mom was making clouds of steam by pouring cup after plastic cup of water into the van’s radiator. My brothers and sisters performed tag in a triangle of scrawny grass. Though my household didn’t usually purchase books (costly), for some motive we’d just lately visited a bookstore, the place I selected The First 4 Books of Poems (four-for-one appealed to my sense of worth). I’d learn poetry earlier than, but it surely was this explicit encounter with poetry, at nightfall in excessive summer season surrounded by the odor of gasoline, that remade me. Louise thought it humorous—it’s humorous—that each of my introductions to her occurred at Midwestern gasoline stations.

Her books, now piled beside me, embody one thing like six a long time of moods and conditions. As a poet, she is each mounted and fluid. Change, I consider, was one among her deepest pursuits and drives. “As quickly as I can place myself and describe myself—I would like instantly to do the other factor,” she informed an interviewer. Every e-book responds to some facet of the earlier. The distinctiveness of her strains—the highly effective readability of her ideas—obscures, I feel, that she is a grasp of personae, and it’s attainable, a minimum of from Ararat onward, to know the books as each lyric and dramatic. The poems are made so subtly it’s straightforward to overlook that subtlety, like grandeur, is one among her modes. The strains folks usually quote, such because the closing couplet of “Nostos”—“We take a look at the world as soon as, in childhood. / The remainder is reminiscence.”—resound due to their daring assurance. However that conclusion requires the preemptive undermining of the earlier strains: “Fields. Odor of the tall grass, new minimize. / As one expects of a lyric poet.” (Once more, she by no means will get sufficient credit score for being humorous.)

An abiding preoccupation, which compels the modifications from poem to poem, voice to voice, e-book to e-book, is an nervousness about creation. Typically it emerges as an nervousness concerning type: discovering a enough one, coping with the implications of fixing something in phrases, which essentially holds it nonetheless. Typically it’s the worry, lurking or said, that there’ll by no means be one other poem. (“I’m speaking an excessive amount of,” she mentioned to me just lately. “However you’re our nice poet of silence,” I teased her.) The best nervousness, nevertheless, issues whether or not the factor created—the poem—will do justice to creation itself.

After I realized she had died, I used to be sitting on my mattress, a pink pocket book in my lap. In that dazed revolt that’s grief’s first incarnation, I wrote, You wrote my life, after which I corrected, You wrote throughout my life, after which I corrected that correction: You wrote all by way of my life, and now I appropriate with a line I do know I’ll appropriate once more until I’m useless, too: You wrote me into my life.

“Sentimental,” I can hear her saying, with a grimace.

***

Within the years since I met Louise as an individual, not solely as a poet, I’ve felt as if we have been certain by an affinity that didn’t all the time emerge from the perfect components of both of our souls. That we each casually use the phrase soul is one piece of that affinity. However there was additionally a sharpness, a darkness, an ironic eye turned on the self and the world—these tied us collectively as a lot because the appreciation of absurdity, the frustration with language, the worry of silence, the devotion to artwork, the fervour for sensory expertise and for ardour itself, in its manifold varieties. Manifold, a phrase that I affiliate along with her, as a result of its most excellent use could also be within the first poem by her that I learn, “The Drowned Youngsters”—who’re perpetually lifted within the pond’s “manifold darkish arms.”

Louise had so many pals, so many college students, and I believe that many really feel an identical sense of affinity. Her perceptiveness made her, I feel, unusually able to forming intense connections. It may additionally (right here, Louise, I supply a counterpoint, a concord) make her unkindness particularly devastating.

After I look again, I hint what seems like her love for me. She learn. She listened. She critiqued. She inspired. She nagged. Her religion in me exceeded my religion in myself. She supported me throughout a psychiatric hospitalization, and after my brother’s loss of life. In flip I attempted to like her, to know her, to reside, and to jot down.

After I heard she was sick, and earlier than I heard she died, I copied down a passage from Digicam Lucida, by which Roland Barthes rebels in opposition to the applying of any class to his particular grief over the absence of his particular maman: “what I’ve misplaced just isn’t a Determine (the Mom), however a being; and never a being, however a high quality (a soul): not the indispensable, however the irreplaceable.” My first, flailing, infantile thought when she informed me that she was sick: I can’t do that with out you. I nonetheless am unsure what I meant by this (poetry? life?) however I do know what I meant by you. You, Louise, who would hate this complete factor.

I final noticed her—how can “final” actually imply “final”?—on the finish of August, once I spent a number of days visiting her in Vermont. For a lot of that point we talked as I drove her by way of a panorama of a stable inexperienced fortified by the wild rains that had flooded Montpelier, and spoiled her backyard. In a labyrinthine vintage retailer, we sat for a pair hours in a matched pair of damasked armchairs, discussing the historical past of {our relationships} with magnificence (in folks, in objects, on the planet). In Plainfield, I inched the automotive ahead slowly sufficient for her to level out each place of previous significance, and outdoors the home the place she wrote The Wild Iris, we talked about our terror of how love works on the lover, how pathetic it makes you. After I started the lengthy drive again to New York, we have been in the midst of many conversations, which we mentioned we’d decide up quickly, subsequent time we noticed one another, and the following time, after we would end our conversations, then I might purchase her dinner, for a change, a extremely glorious dinner, acceptable to her gourmand style. As I write this, the meantime disappears. We’re sitting throughout from one another at a eating desk. Sundown behind her, which implies night time is already behind me. The silence that follows a bout of laughter has settled on us. The wine she selected is sort of gone. She asks, “Do you suppose anybody would anticipate us to snigger as a lot as we do?” And since I’m once more answering, I do know that she was proper, in “Lament,” to conclude that “this, this, is the that means of / ‘a lucky life’: it means / to exist within the current.”

Elisa Gonzalez is a poet, fiction author, and essayist. Her debut assortment of poetry is Grand Tour.