James Schuyler on the Chelsea Resort, 1990. {Photograph} by Chris Felver.

I’d deliberate to put in writing about one in all my favourite James Schuyler poems in time for the centenary of his start final November, however

Previous is previous, and if one

remembers what one meant

to do and by no means did, is

to not have thought to do

sufficient? Like that gather-

ing of one in all every I

deliberate, to assemble one

of every form of clover,

daisy, paintbrush that

grew in that area

the cabin stood in and

research them one afternoon

earlier than they wilted. Previous

is previous. I salute

that numerous area.

The tiny, beloved “Salute”—which isn’t the poem that I imply to debate—each gathers and separates, does after which undoes what the poem says Schuyler meant to do however by no means did. (And isn’t this, the play of meeting and disassembly, to a sure extent simply what verse is? How half and complete relate or fail to because the poem unfolds in time is a fundamental drama of poetic kind.) Schuyler’s enjambments—directly distinct and tender, like the sting of a leaflet or the margin of a petal—are websites of hesitation the place meanings acquire earlier than they’re scattered or revised.

For a second I hear “Like that gather-” as an crucial: Do it that means, collect in that method, earlier than the noun “gathering” gathers throughout the margin. I briefly hear “one in all every I”—every of us is a area of assorted “I”s—as the item of the gathering earlier than it turns into the topic who has “deliberate” it. (The comparative metrical regularity of “Like that gathering of one in all every I deliberate,” the alternating stresses, haunts these enjambments, a prosodic previous or body the poem salutes and breaks with, breaks up.) I’m at all times barely stunned when “to assemble one,” on the finish of the seventh line, repeats “of every,” versus modifying a brand new particular noun, on the left margin of line eight. (This break makes me really feel the stress or oscillation between “every” and “type”—and a sort is a gathering of likes—between the discrete specimen and the category for which it stands, the actual dissolving into exemplarity, if you write it down.)

There may be a lot repetition within the quick poem—“one,” as an example, seems 5 occasions, undoing the singularity; right here it’s an individual, right here a quantity, right here a particular afternoon. It’s as if the vocabulary had been being restricted, held fixed, so Schuyler can take a look at what relineation may do to the music and which means, “learning” every tentative association of the small phrases he’s gathered. (There’s a sense of provisionality and casualness and plain speech right here and most in every single place in Schuyler, nevertheless it coexists with the implication of archival formal order; there’s the prosodic backdrop I discussed, however there’s additionally the close to syllabic regularity of the strains—eight of the fifteen are six syllables, as an example—or that lengthy u sound on the finish of the fourth and twelfth and fourteenth line, which supplies some sonic structure.)

After which there’s the essential repetition of the tautology “Previous is previous,” a repetition (of a repetition) that affirms for me that the poem is testing the way it may make distinction out of sameness, reworking the phrase by delaying the verb throughout the break when it recurs. The previous returns with a distinction: “Previous is previous” doesn’t equal “Previous / is previous.” A lot relies on that nonidentity. The latter occasion of the phrase, whereas nonetheless melancholy, has a heartbeat: the silence on the break is felt, possesses its personal length, the shape occurs within the renewable current tense of studying, in order that—to take a phrase from Jack Spicer—the “factor language” of the poem overcomes its content material, and the road not laments time that’s merely misplaced. I don’t imply to make the poem sound triumphant, to indicate that point is unequivocally regained, for a “salute” could be a salutation or an elegy (as in a funeral salute), and it’s the oscillation—I’m going to run with the phrase—between these modes that lends the poem its tender pressure. Nonetheless, one is grateful Schuyler solely meant to assemble specimens in order that the sphere, in all its selection, is unbroken.

***

However I meant to speak about one other poem, one other flower, “The Bluet,” in time for his hundredth birthday.

THE BLUET

And is it stamina

that unseasonably freaks

forth a bluet, a

Quaker woman, by

the lake? So small,

a drop of sky that

splashed and held,

four-petaled, creamy

in its throat. The woods

round had been brown,

the air crisp as a

Carr’s desk water

biscuit and smelt of

cider. There have been frost

apples on the bushes in

the sphere beneath the home.

The pond was nonetheless, then

broke right into a ripple.

The hills, the leaves that

haven’t but fallen

are deep and oriental

rug colours. Brown leaves

within the woods set off

grey trunks of bushes.

However that bluet was

the main target of all of it: final

spring, subsequent spring, what

does it matter? Sudden

as a tear when somebody

reads a poem you wrote

for him: “It’s this line

right here.” That bluet breaks

me up, tiny spring flower

late, late in dour October.

As an alternative of starting with the previous, we begin with “and,” in medias res, evoking the epic the poem clearly isn’t, though the query of stamina—of effort and its prolongation—appears consonant with the generic marker, and, from the attitude of one thing “so small,” unseasonably pushing by way of the soil is fairly epic.

It’s outstanding how a lot erotic or at the least probably erotic language the poem begins with, however with out intercourse overwhelming the lexical area. I dare you to place the next phrases in a Google search: “stamina,” “freaks,” “splashed,” “creamy,” “throat.” All this makes the “Quaker woman” sound a bit of like a freak, perhaps in drag, however then such a studying is reduce by the proximity of “woman” to “lake,” which makes it literary, idealizing, Arthurian (epic). So there’s oscillation between scales, together with of style, and between the carnal and the courtly. After which “stamina” can be a plural of stamen, which is the pollen-producing male reproductive organ of the Quaker woman (of the Lake) in query. The grammar of the road retains the botanical sexual sense from being the first one, nevertheless it’s there. The phrases themselves waver between being plain and literary, thingly and allusive, whereas the diction is directly talky and taut, a bit of heightened.

I like that “held” on the finish of the seventh line, how “held” simply manages to carry the splash of sky earlier than it spills over the precipice of the precise margin. You may virtually see it tremble with the hassle, buttressed by the comma. All three of the phrases within the line finish in d, and all of the letters of “held” are held by “splashed,” as in the event that they splashed out of the longer phrase. “[P]etaled” within the subsequent line appears to synthesize the sounds of “splashed” and “held,” and what a stunning definition of a petal: a splash of colour that held, that holds, till it withers. (The l sounds of “petaled” will later be held nonetheless in “nonetheless,” after resting in “apple,” then break right into a “ripple,” after which proceed to ripple by way of the poem, viz. “oriental.”)

The “paintbrush,” that essential form of flower in “Salute,” is so referred to as as a result of it’s mentioned to resemble brushes dipped in shiny purple or orange-yellow paint. And I believe the bluet on this poem is each an precise blue flower on this planet and, invariably, the blue flower of artwork, the Blaue Blume of Novalis. There may be one other essential oscillation, then, between nature and tradition, between a specific blossom and a poetic image. Schuyler himself may discourage this studying: “All issues are actual / nobody a logo,” begins the poem “Letter to a Pal: Who’s Nancy Daum?” and in an interview Schuyler mentioned: “I’m not … within the concept of the rose because it happens on and on all through literature, I’m involved in roses, in Georg Arends, and a brand new rose.” However even in (these very Williams-like) disavowals of the flower as image, there’s a blurry boundary between nature and conference: the “new rose” is introduced into existence through the horticulturalist’s artwork, the flower is called for its “creator” (Georg Arends), it’s decorative. And what may very well be extra literary than to be fascinated by the title of the rose, obsessed as Schuyler was by the nomenclature of flowers? (Schuyler’s “Horse Chestnut Timber and Roses,” for instance, is as a lot a celebration of the names of cultivars because the flowers themselves.) So whereas the flower is rarely merely a logo in Schuyler, it may very well be mentioned to represent the assembly of nature and tradition, of the given and the made, of the discrete issues and the sorts that language makes.

Perhaps it’s extra to the purpose to say that Schuyler’s description of the flower transforms it into artwork, and that this type of transformation is his signature poetic exercise; it occurs repeatedly in his poems: he describes what he sees earlier than him as if it had been a portray in order that commentary of the pure world turns into ekphrasis. That’s why—to skip down a bit of—the leaves are likened to a rug, crossing inside and outside, nature and tradition, and people leaves “set off” the grey the best way a painter or sharp dresser makes use of one colour to set off or complement one other, why the air is sort of a made factor, too, if one you eat, and why the bluet is named “the main target,” the best way artwork critics say one thing is “the main target of the composition.” Schuyler’s phrases are paintbrushes, what he describes turns into a portray (although he treats it as already painted)—paint, a medium that splashes after which holds. There are examples of this in every single place in his books. In “Evenings in Vermont,” as an example, a rug once more mediates between inside and outdoors, artwork and nature: “I research / the sample in a purple rug, arabesques / and squares, and one purple streak / lies within the west, over the ridge.” In “Scarlet Tanager,” the chook within the tree supplies “the purple contact inexperienced / cries out for.” In “A Grey Thought,” “a darkish thick inexperienced” is “laid in layers on / the spruce …” And so forth. Touches, layerings: colour as paint, pure phenomena perceived as artwork.

There’s a gentle modernism right here that reenchants the world—barely, briefly—by changing what’s merely there into vital kind in order that the panorama turns into a historical past of small inventive selections. Whose selections, whose touches and layerings? Not God’s, and never fairly Stevens’s “main man” reinvesting the world with which means by way of the powers of poetic creativeness. However not not that both: It’s extra like a minor man, who has checked out a number of good work, and likewise seemed—in a number of ache—out of the window (one other body) of Payne Whitney (the psychological hospital the place Schuyler spent a while; “Salute” was written in Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains). Williams mentioned “no concepts however in issues,” Stevens mentioned that poetry’s energy is “the ability of the thoughts over the chances of issues,” Schuyler oscillates between them. Schuyler is nearer to Williams within the consideration to mundane speech and the mundane issues at hand (e.g., a Carr’s cracker; which isn’t to say Stevens had no concern with dailiness, or “extraordinary evenings”), crucially nearer to Williams in enjambment because the foundational poetic approach (I consider Spring and All: “in order that to have interaction roses / turns into a geometry—”). However Schuyler is a bit more like Stevens within the mission of imaginative redescription: bluet, blue flower, blue guitar. The literary family tree doesn’t actually matter (and one may configure it in another way); my level is that the magic of Schuyler is that you simply really feel nature changing into artwork as you learn. Otherwise you really feel the hassle to make it so, its fluctuations, typically its failure.

After all, he’s not describing an precise painted picture, however making a poetic one; Schuyler is composing the scene, the small selections are his, nevertheless it appears like he’s participating one other medium, and so the poet’s act of creation is smuggled in, as if he had been simply anyone else’s illustration of the view. This offers his voice a form of secondariness, a form of modesty—I’m not the visionary, I’m simply reviewing the visions for Artwork Information (the place he was an affiliate editor). This partly accounts for a way his tone is concurrently matter of truth and metamorphic. Schuyler makes his writing seem to be he’s “studying” a portray, however this type of secondariness really turns into a species of immediacy as a result of his ekphrastic language additionally describes his personal verbal kind, the poem we’re studying: the splashes and holds, the falls from margin to margin. Which means Schuyler’s “studying” and our studying of Schuyler correspond, our acts of consideration are calibrated throughout time.

(I assume it’s apparent that I’m not suggesting Schuyler is the one poet who makes the world seem to be a made factor, like artwork, or that he’s the one poet whose unfolding perceptions are transferred to poetic kind in order that, as we attend to his work, creator and reader are in a way coeval; quite the opposite, some model of such transformations and transfers are current within the writing I really like throughout genres and eras. However that’s why I’m attempting to explain and rejoice Schuyler’s particular, quiet fashion, his strategies and tonalities; in his minor means, he makes contact with one thing elementary.)

(And right here I’d point out that, whereas they’re very completely different writers, Schuyler’s tendency to reframe nature as artwork is a attribute shared together with his pal, the sensible Barbara Visitor, and whereas Schuyler’s talkiness and dailiness have extra in frequent with O’Hara—who couldn’t, as he wrote in “Meditations in an Emergency,” “even take pleasure in a blade of grass” until he knew “there’s a subway useful, or a report retailer or another signal that individuals don’t completely remorse life”—Schuyler is in some ways nearer to Visitor in his tendency to redescribe nature as tradition, to current the merely contingent as organized. As with Schuyler, this transformation in Visitor typically includes a window—a body by way of/wherein pure phenomena may seem because the touches or layerings of the compositional. Artwork and home windows are sometimes paired in Visitor, as in her nice poem, “The View from Kandinsky’s Window,” or the title of her collected writings on artwork, Dürer within the Window. Has somebody written an essay on the home windows of The New York College? I consider Ashbery’s “October on the Window” or “The New Larger”—“… the window the place / the surface crept away”—and O’Hara’s small “Home windows”: “this area so clear and blue / doesn’t care what we put // into it …” A method Schuyler has a major aesthetic affiliation with these different writers—versus only a social one—is in his experiments with what one can put into the window: “put into” as a result of the body of the window stands for the transformation of contingency into composition. For his half, Schuyler is obvious and modest—generally to the purpose of quiet comedy—concerning the centrality of the window to his compositions. Interviews get solutions like this once they ask him about his methodology: “[T]listed below are issues all by way of the poem which are really what I’m seeing out the window in Southampton,” “The issues described in it are what I used to be seeing out the window in the home in Maine,” and so forth.)

However to return to lateness and its undoing: “Previous is previous,” “late, late”—belatedness is the standard theme that “Salute” and “The Bluet” indulge and, of their small means, defeat or, higher, gently droop. The bluet might be assigned to the final spring or the following one, that doesn’t matter, because it’s occurring now, surprising as a “tear” (rhymes with pricey) that we’re not solely positive isn’t a “tear” (rhymes with dare, just like the torn or jagged proper margin of a poem) till it’s tuned—made decisively lacrymal—by the “right here” arriving on the left margin within the third to final line. “Tear” itself stays suspended between being a drop (recalling the drop of sky the flower holds) or one thing lease “in order to go away ragged or irregular edges” till it drops over the irregular fringe of the poem. “It’s this line / right here.”

Besides it isn’t, or it’s and isn’t: “this” refers (at the least at first) to the fourth to final line, the “right here” begins the third to final. The road concerning the line that triggered the tear is torn throughout the margin, it’s in each locations directly, or it’s in neither place, a Schrödinger’s cat of a line. Final line, subsequent line, what does it matter? A method it issues is that the formal irony—the best way the road break renders “this” and “right here” paradoxical, undecidable—implies that these deictics appear finally to consult with the unnameable break itself, that little second of hesitation that we use a virgule to indicate in prose, a felt silence, the white area that’s the drop of sky or teardrop not held or contained inside the phrases of the poem; emotion is as a substitute expressed by formal movement. (Dramas of lineation are additional heightened by the truth that this poem—like “Salute”—is a single stanza; there are not any bigger breaks, no different species of segmentation, competing with the irregular margins.) “Previous is / previous,” “It’s this line / right here”—all of poetry is for me in these little delays, catches within the breath, delays that each formally enact belatedness and, by making it felt within the embodied current tense of studying, undo it.

In each situations—“Previous is previous” is a cliche; “It’s this line / right here” is quoted speech from a pal or lover—Schuyler is breaking apart obtained phrases, discovered language, displaying how lineation, how artwork, can alter the given, how secondariness isn’t simply lateness however a possibility for imaginative transformation. The individual Schuyler quotes has to level to the road that strikes him; it escapes description or paraphrase. (I consider the “him,” regardless of the biographical details, as a lover due to the erotic language earlier within the poem, the place the drops of sky, why not simply say it, may also be sexual fluid.) It’s a beautiful suggestions loop of studying and writing (or a Möbius strip wherein the 2 turn out to be a single apply): Schuyler writes the poem that strikes the lover, Schuyler is moved that the lover is moved, the lover’s language about being moved—indicating a line we by no means see—is then so movingly organized, damaged up in a second poem that breaks me up every time I learn it. So mere belatedness is changed with a series of feeling to which we readers can add hyperlinks. One other poet would sound self-aggrandizing—look how my poems transfer males to tears!—however what I hear is Schuyler’s melancholy gratitude, admiration, for that openness, receptivity, which his poem communicates, makes accessible within the “/ right here” of poetry. (Schuyler’s “this line / right here”—the indication with out citation of the road in query—jogs my memory of Denise Levertov’s “The Secret,” one other poem wherein the poet is moved by readers’ capability to be moved, and wherein the journey of enjambment—the best way poetic kind occurs—is widely known for its inexhaustibility: “Two women uncover / the key of life / in a sudden line of / poetry. // I who don’t know the / secret wrote / the road …”) That “/ right here” is what I hear described in Schuyler’s thanks poem to Kenward Elmslie for the present of a letter opener in “A Stone Knife,” a poem that remembers “Salute,” and that each celebrates and enacts the renewable “shock” of poetic kind:

the shock is that

the shock, as soon as

previous, is at all times there:

which to take pleasure in is

to not devour. The un-

recapturable returns …

***

Schuyler’s breaks, his sense of the road, are treasured to me, and but he was matter of truth to the purpose of dismissiveness about how they got here to be. “I don’t actually know the way I occurred to get into writing such very skinny poems,” he informed an interviewer. “I used to be writing in very small notebooks that I carried round with me, and it was simpler simply to put in writing like that …”

I believe I began it as a result of I wrote in John Ashbery’s front room—I used to be on my solution to Southampton and Vermont—a poem referred to as “Who’s Nancy Daum?,” which is in The Crystal Lithium, and I had written that in a really small pocket book, pondering that I may rearrange the strains in the event that they weren’t lengthy sufficient for no matter strains I meant. It was the form of pocket book you carry in your jacket pocket. After which once I got here to kind it up, I assumed I would depart it the best way it was, in jagged strains.

Some really feel that is proof that Schuyler’s poems are haphazardly composed, and so it’s some form of misreading to be moved by this or that “line / right here,” however I discover this informal account of lineation solely suitable with the advanced and delicate results his enjambments produce. When a painter decides on the scale of a canvas to stretch, we don’t then low cost each different compositional resolution she makes as random. That’s how I consider these notebooks wherein so lots of the poems I really like had been made: that Schuyler was typically negotiating a miniature, goal margin in actual time as his acts of commentary unfolded strikes me as one other means we’d meaningfully converse of him as painterly (typically a supremely meaningless adjective for a poet), one other means the presence of a body structured his compositional approach, whether or not he took the pocket book en plein air or labored indoors, trying forwards and backwards from pocket book to window. Pocket book and window, his two frames. It makes me consider one in all my favourite of his uncollected poems, one other poem that echoes “Salute,” and its pasts which are and aren’t previous: “A Blue Shadow Portray,” devoted to Fairfield Porter, that begins by describing “a night actual as paint on canvas.” When the painter on this poem hundreds his brush and concentrates, it’s “as if he noticed neither the work in hand nor the topic”—he makes fast, maybe solely semi-conscious selections within the time of composition, thereby managing to retailer a few of that point in artwork, the place it awaits us: “The day / is passing, is previous: a number of and immutable got here to reside / on a small rectangular of stretched canvas … ”

***

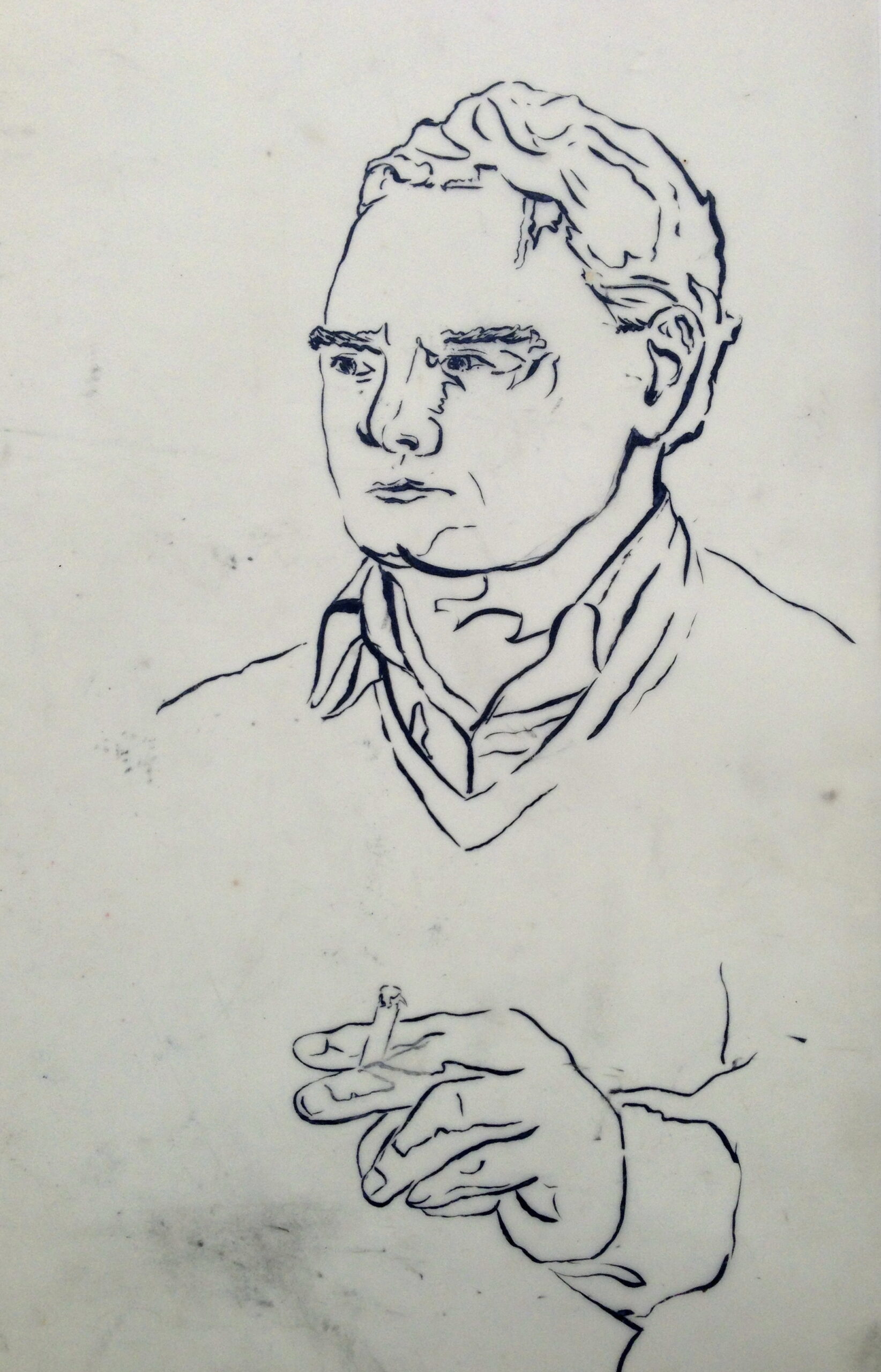

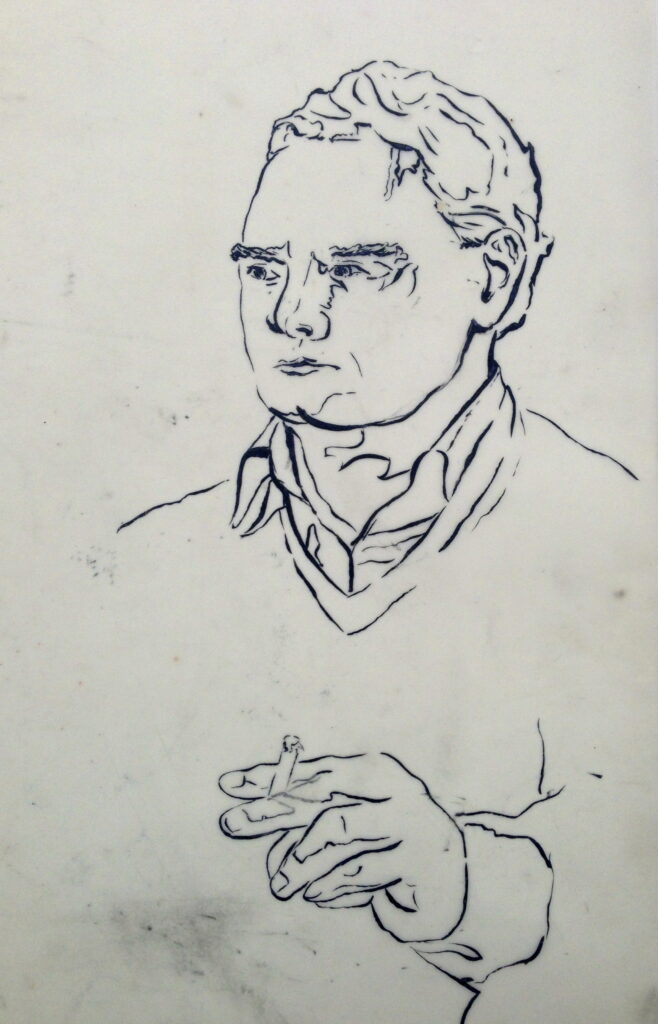

Darragh Park, Portrait of James Schuyler, 1996, ink on acetate, 10 x 8″. Personal assortment.

There are, in fact, a variety of kinds (and moods and modes) in Schuyler—lengthy poems, poems with very lengthy strains, poems that incorporate a number of white area, to not point out the novels—however my Schuyler will at all times be the miniaturist of “Salute” or “The Bluet” (or “Korean Mums,” and different flowers). In these poems specifically Schuyler possesses a form of tender Midas contact wherein all the things his eye alights on turns into artwork, turns into composition as he describes it, after which his personal compositional selections—particularly his enjambments, his surprising tears (rhymes with stairs)–convey our consideration in step with his, in order that we really feel we’re trying collectively throughout time, and so the previous isn’t merely previous, however at all times current within the kind, accessible as the current of kind, which is rarely consumed.

However once more I really feel I’m making him sound too triumphant, as if losses had been finally overcome. I say it’s a Midas contact as a result of typically in Schuyler the poem, the artwork, is a doc of emotional struggling and isolation. The drama of half and complete so central to poetry can be a drama, in Schuyler, of holding it collectively; the specter of falling aside is emotional, not simply technical. (I’ve at all times been struck by the injunction: “Compose your self,” a merciless and revealing factor to say to an upset individual.) Generally the strains appear to tremble with the hassle; generally the will to convey the surface inside, to press nature into artwork, has a quiet desperation, as in these final strains of the final poem I’ll quote in its entirety, “February 13, 1975,” one of many poems written in Payne Whitney:

Tomorrow is St. Valentine’s:

tomorrow I’ll take into consideration

that. At all times nervous, even

after sleep I’d like

to climb again into. The solar

shines on yesterday’s new

fallen snow and yestereven

it turned the world to pink

and rose and metal blue

buildings. Helene is stressed:

leaving quickly. And what then

will I do with myself? Some-

one is watching morning

TV. I’m not decreased to that

but. I want one may press

snowflakes in a guide like flowers.

So lots of the oscillations I’ve described are occurring softly right here. Do you learn the primary line as talky, as matter of truth, or as iambic tetrameter, evoking a conventional prosody that the poem will then break up? (I hear the final line of the poem as echoing and revising the meter; to my ear, it’s trochaic tetrameter, although my associates hear it in another way.) There may be the plain speech (and ghosts of made phrases: nothing new beneath the solar; “yesterday’s information” is sort of there within the sixth line) coexisting with the archaic literariness of “yestereven.” This casualness, the talkiness, can be reduce by the sonic relays—”into,” “new,” “blue,” “quickly,” “do,” “decreased”—that assist maintain the shape collectively. The world turns into a made factor when the solar turns it into “metal blue / buildings.” (And even the small shock of “TV” on the left margin of the third to final line, the place “morning” reveals itself to be an adjective and never the item of somebody’s watching, is one other occasion of nature changing into tradition.) And once more we have now the temporal tensions, glitches throughout the margins, as in “yesterday’s new / fallen snow.” What was new yesterday is already outdated, the brand new fallen is the not too long ago belated, particularly in case you make the “new” pause for a second earlier than it falls. The poem (like each poem?) is late and early (like a spring flower in October) as it’s written in lonely anticipation of tomorrow, Valentine’s Day, and all this results in the fantasy of artwork current exterior of time, of a “but” that may very well be pressed, the snow preserved between the pages like a flower one deliberate to assemble.

And isn’t to have thought to do / sufficient?

Ben Lerner’s most up-to-date guide is The Lights. This speak was delivered as a part of a brand new semiannual lecture sequence on the Poetry Society of America in Brooklyn.