All pictures courtesy of the creator.

A type of life that retains itself in relation to a poetic observe, nonetheless that may be, is all the time within the studio, all the time in its studio.

Its—however in what approach try this place and observe belong to it? Isn’t the alternative true—that this type of life is on the mercy of its studio?

***

Within the mess of papers and books, open or piled upon each other, within the disordered scene of brushes and paints, canvases leaning in opposition to the wall, the studio preserves the tough drafts of creation; it information the traces of the arduous course of main from potentiality to behave, from the hand that writes to the written web page, from the palette to the portray. The studio is the picture of potentiality—of the author’s potentiality to jot down, of the painter’s or sculptor’s potentiality to color or sculpt. Making an attempt to explain one’s personal studio thus means trying to explain the modes and types of one’s personal potentiality—a process that’s, at the least on first look, inconceivable.

***

How does one have a potentiality? One can not have a potentiality; one can solely inhabit it.

***

Habito is a frequentative of habeo: to inhabit is a particular mode of getting, a having so intense that it’s now not possession in any respect. By dint of getting one thing, we inhabit it, we belong to it.

***

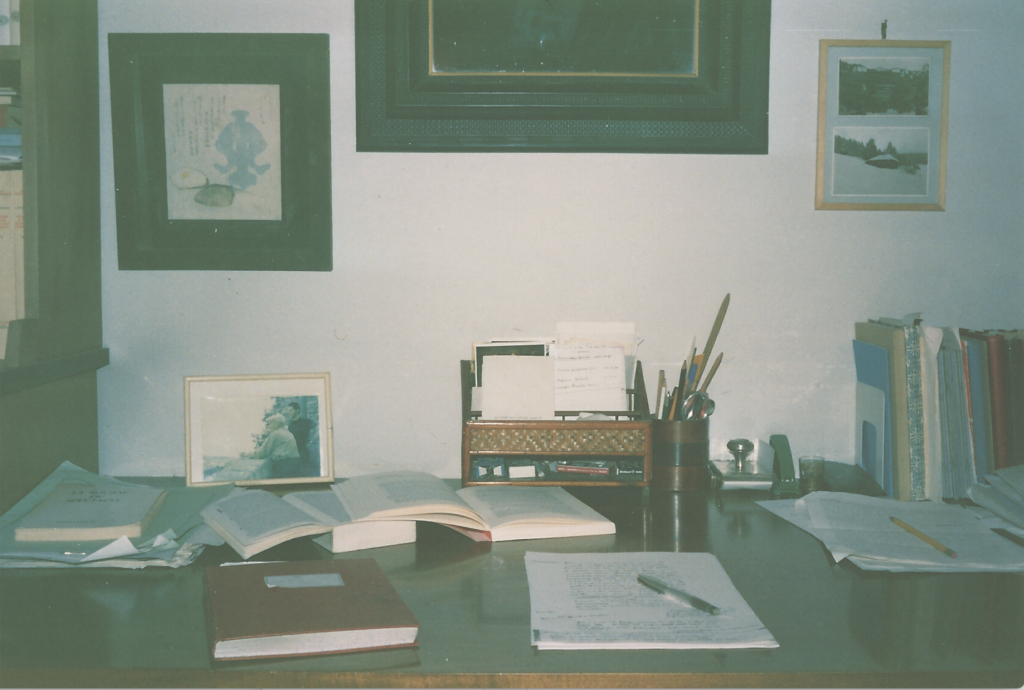

The objects of my studio have remained the identical, and years later within the pictures of them elsewhere and cities, they appear unchanged. The studio is the type of its inhabiting—how may it change?

***

Within the wicker letter tray in opposition to the wall on the heart of the desk in each my studio in Rome and the one in Venice, on the left there’s an invite to the dinner celebrating Jean Beaufret’s seventieth birthday, on the entrance of which is written this line from Simone Weil: “Un homme qui a quelque selected de nouveau à dire ne peut être d’abord écouté que de ceux qui l’aiment.” The invitation carries the date Might 22, 1977. Since then, it has all the time remained on my desk.

***

One is aware of one thing provided that one loves it—or as Elsa would say, “just one who loves is aware of.” The Indo-European root meaning “to know” is a homonym for the one meaning “to be born.” To know [conoscere] means to be born collectively, to be generated or regenerated by the factor identified. This, and nothing however this, is the that means of loving. And but, it’s exactly one of these love that’s so tough to seek out amongst those that imagine they know. In reality, the alternative typically happens—that those that dedicate themselves to the examine of a author or an object find yourself growing a sense of superiority in direction of them, virtually a type of contempt. That is why it’s best to expunge from the verb “to know” all merely cognitive claims (cognitio in Latin is initially a authorized time period that means the procedures for a decide’s inquiry). For my very own half, I don’t suppose we are able to choose up a guide we love with out feeling our coronary heart racing, or really know a creature or factor with out being reborn in them and with them.

***

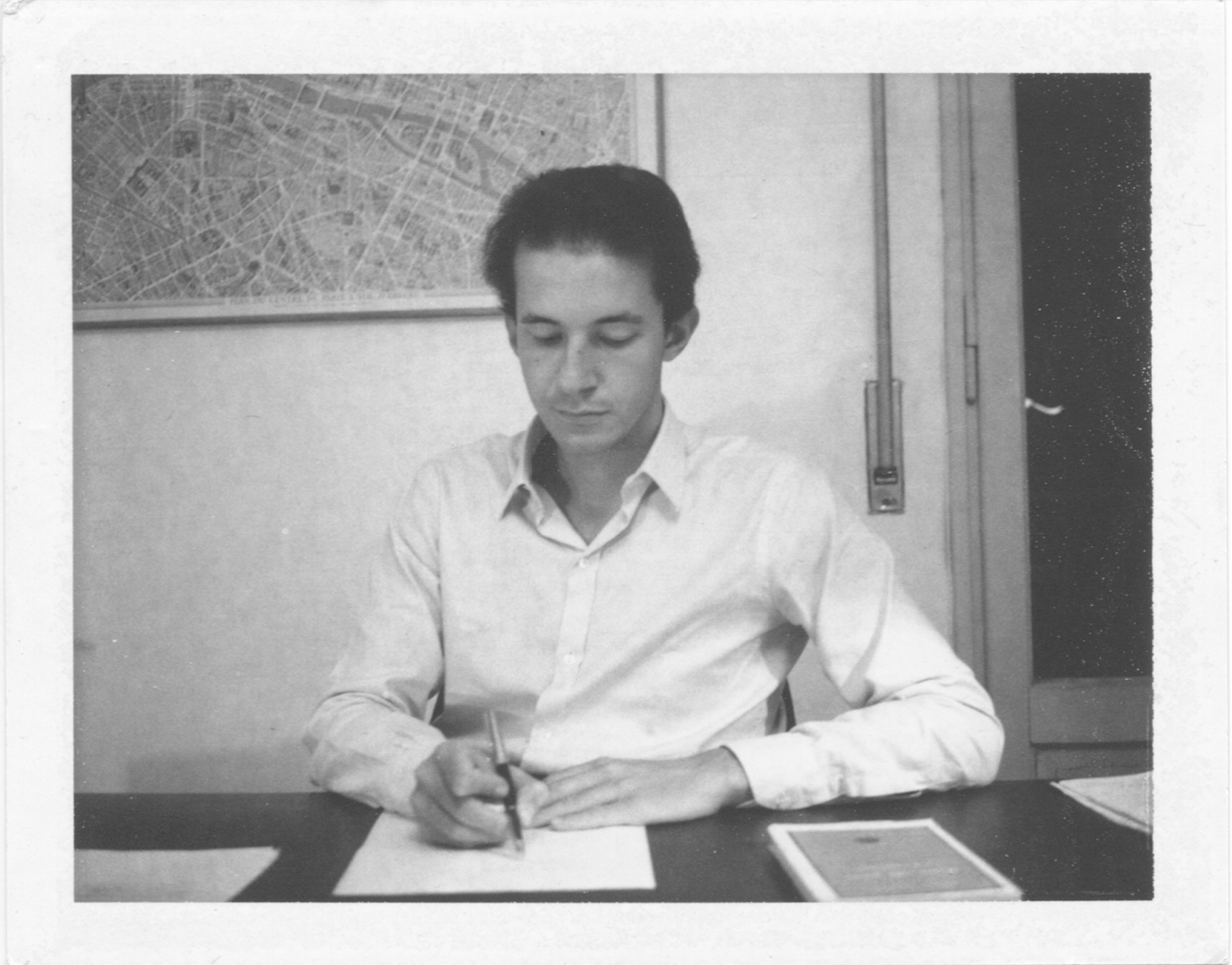

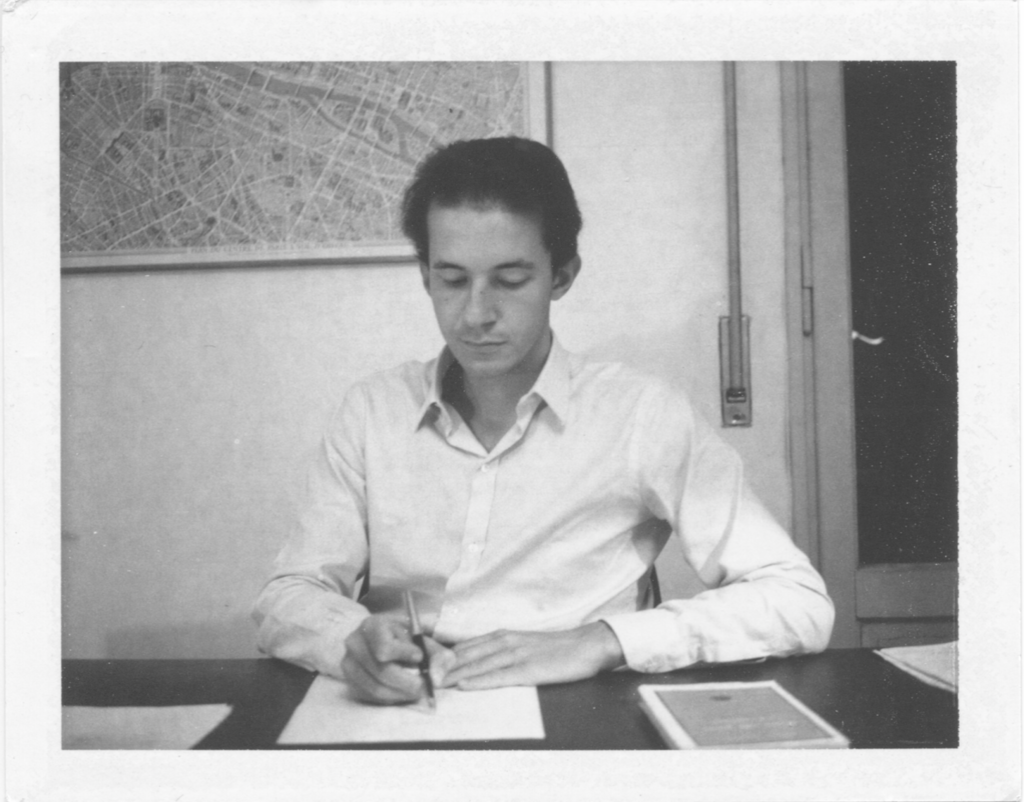

The {photograph} with Heidegger to my left, in my studio on Vicolo del Giglio in Rome, was taken within the countryside of Vaucluse throughout one of many walks that punctuated the primary seminar at Le Thor in 1966. At a distance of half a century, I can not neglect the panorama of Provence immersed within the September gentle, the white rocks of the boris, the good, steep hump of Mont Ventoux, the ruins of Sade’s Château de Lacoste perched on the rocks. And the feverish, star-pierced night time sky, which the moist gauze of the Milky Method appeared to wish to soothe. It’s maybe the primary place I needed to cover my coronary heart—and there, untouched and unripe because it was, my coronary heart should have remained, even when I may now not say the place—maybe below a boulder in Saumane, in a cabin of Le Rebanqué, or within the backyard of the little resort the place Heidegger held his seminar each morning.

***

What did the assembly with Heidegger in Provence imply to me? I definitely can not separate it from the place the place occurred—his face directly light and stern, intense and uncompromising eyes that I’ve by no means seen elsewhere save in a dream. In life there are occasions and conferences which can be so decisive that it’s inconceivable for them to enter into actuality fully. They occur, to make certain, and the mark out the trail—however they by no means stop to occur, so to talk. Steady conferences, on this sense, as theologians say that God by no means ceases to create the world, that there’s a steady creation of the world. These conferences by no means stop to accompany us till the top. They’re a part of what stays unfinished in a life, what goes past it. And what goes past life is what stays of it.

***

I keep in mind, within the dilapidated church of Thouzon, which we visited on certainly one of our excursions in Vaucluse, the Cathar dove carved contained in the architrave of a window in such a approach that nobody may see it with out wanting within the reverse of the standard path.

***

That small group of males who, within the {photograph} from September 1966, stroll collectively towards Thouzon—what ever grew to become of it? Every in his personal approach had roughly consciously meant to make one thing of his life—the 2 seen from the again on the appropriate are René Char and Heidegger, behind them myself and Dominique—what grew to become of them, what grew to become of us? Two have been useless a very long time; the opposite two are, as they are saying, getting on in years (getting on towards what?). What issues right here will not be work, however life. As a result of on that late sunny afternoon (the shadows are lengthy) they had been alive and felt it, every intent in his ideas, that’s, within the bit of fine that he had glimpsed. What has change into of that good, whereby thought and life weren’t but divided, whereby the sensation of the solar on the pores and skin and the shadow of phrases within the thoughts so fortunately merged?

***

Smara in Sanskrit means each love and reminiscence. We love somebody as a result of we keep in mind them and, vice versa, we keep in mind as a result of we love. In loving we keep in mind and in remembering we love, and ultimately we love the reminiscence—that’s, love itself—and we keep in mind love—that’s, reminiscence itself. That is why loving means being unable to neglect, being unable to get a face, a gesture, a lightweight out of your thoughts. However in reality it additionally implies that we are able to now not have a reminiscence of it, that love is past reminiscence, immemorably, ceaselessly current.

***

A web page from Nicola Chiaromonte’s notebooks comprises a unprecedented meditation on what stays of a life. For him the important difficulty will not be what we’ve or haven’t had—the true query is, reasonably, “what stays? . . . what stays of all the times and years that we lived as we may, that’s, lived in response to a necessity whose legislation we can not even now decipher, however on the identical time lived because it occurred, which is to say, by likelihood?” The reply is that what stays, if it stays, is “that which one is, that which one was: the reminiscence of getting been ‘lovely,’ as Plotinus would say, and the flexibility to maintain it alive even now. Love stays, if one felt it, the passion for noble actions, for the traces of the Aristocracy and valor discovered within the dross of life. What stays, if it stays, is the flexibility to carry that what was good was good, what was dangerous was dangerous, and that nothing one would possibly do can change that. What stays is what was, what deserves to proceed and final, what stays.”

The reply appears so clear and forthright that the phrases that conclude the temporary meditation move unobserved: “And of us, of that Ego from which we are able to by no means detach ourselves and which we are able to by no means abjure, nothing stays.” And but, I imagine that these last, quiet phrases lend sense to the reply that precedes them. The great—even when Chiaromonte insists on its “staying” and “lasting”—will not be a substance with no relation to our witnessing of it—reasonably, solely this “of us nothing stays” ensures that one thing good stays. The great is in some way indiscernible from our cancelling ourselves in it; it lives solely by the seal and arabesque that our disappearance marks upon it. That is why we can not detach ourselves from ourselves or abjure ourselves. Who’s “I”? Who’re “we”? Solely this vanishing, this holding our breath for one thing larger that, nonetheless, attracts life and inspiration from our bated breath. And nothing says extra, nothing is extra unmistakably distinctive than that tacit vanishing, nothing extra shifting than that adventurous disappearance.

***

Each life all the time runs alongside two ranges: one seemingly ruled by necessity, even when, as Chiaromonte writes, we can not decipher its legislation, and one other that’s deserted to likelihood and contingency. There isn’t a level in pretending there’s some arcane, demonic concord between these two (that is the hypocritical declare that I used to be by no means in a position to settle for in Goethe), and but, as soon as we handle to have a look at ourselves with out disgust, the 2 ranges, although uncommunicating, don’t exclude or distinction with one another; reasonably, they provide one another a type of serene, reciprocal hospitality. That is the one motive why the skinny material of our life can slip out of our palms virtually imperceptibly, whereas the info and occasions—that’s, the errors—that lay its warp entice all our consideration and all our ineffective care.

***

What accompanies us by means of life can also be what nourishes us. To nourish doesn’t merely imply to make one thing develop; above all, it means to let one thing attain the state to which it naturally tends. The conferences, the readings, and the locations that nourish us assist us to achieve this state. And but, one thing in us resists this maturation and, simply when it appears shut, stubbornly stops and turns again towards the unripe.

A medieval legend about Virgil, whom widespread custom had became a magician, relates that upon realizing he was previous he employed his arts to regain his youth. After having given the required directions to a trustworthy servant, he had himself reduce up into items, salted, and cooked in a pot, warning that nobody ought to look contained in the pot earlier than it was time. However the servant—or, in response to one other model, the emperor—opened the pot too quickly. “On the level,” the legend recounts, “there was seen a wholly bare little one who circled thrice across the tub containing the meat of Virgil after which vanished and of the poet nothing remained.” Recalling this legend within the Diaspalmata, Kierkegaard bitterly feedback, “I dare say that I additionally peered too quickly into the cauldron, into the cauldron of life and the historic course of, and probably won’t ever handle to change into greater than a baby.”

Maturing is letting oneself be cooked by life, letting oneself blindly fall—like a fruit—wherever. Remaining an toddler is desirous to open the pot, desirous to see instantly even what you aren’t supposed to have a look at. However how can one not really feel sympathy for these individuals within the fables who recklessly open the forbidden door.

In her diaries, Etty Hillesum writes {that a} soul may be twelve years previous perpetually. Which means that our recorded age adjustments with time however the soul has an age of its personal that continues to be unchanged from delivery to dying. I don’t know the precisely age of my soul, however it certainly can’t be very previous, in any case no more than 9, judging from the way in which I appear to acknowledge it in my recollections from that age, which have thus remained so vivid and sharp. Yearly that passes, the hole between my recorded age and the age of my soul widens and the sensation of this distinction is an ineliminable a part of the way in which I life my life, of each its nice imbalances and its precarious equilibriums.

***

You may make out the title of the guide mendacity on the left aspect of the desk on Vicolo del Giglio: La société du spectacle by Man Debord. I don’t keep in mind why I used to be rereading it—I first learn it again in 1967, the very yr of its publication. Man and I grew to become associates a few years later, on the finish of the eighties. I keep in mind my first assembly with Man and Alice on the bar of the Lutetia, the instantly intense dialog, the positive settlement about each facet of the political state of affairs. We had each arrived at one and the identical readability, Man ranging from the custom of the inventive avant-gardes, myself from poetry and philosophy. For the primary time I discovered myself talking about politics with out having to bang in opposition to the impediment of ineffective and misguided concepts and writers (in a letter Man wrote to me a while later, certainly one of these glibly exalted writers was soberly liquidated as ce sombre dément d’Althusser . . . ) and the systematic exclusion of those that may have oriented the so-called actions in a much less ruinous path. In any case, it was clear to each of us that the principle impediment barring the way in which to a brand new politics was exactly what remained of the Marxist custom (not of Marx!) and the employees’ motion, which was unwittingly complicit with the enemy it believed it was combatting.

Throughout our subsequent conferences at his home on the rue du Bac, the relentless subtlety—worthy of a magister of Vico de li Strami or a seventeenth-century theologian—with which he analyzed each capital and its two shadows, one Stalinist (the “concentrated spectacle”) and one democratic (the “diffuse spectacle”), by no means ceased to amaze me.

***

The true downside, nonetheless, lay elsewhere—nearer and, on the identical time, extra impenetrable. Already in certainly one of his first movies Man had evoked “that clandestinity of personal life relating to which we possess nothing however pitiful paperwork.” It was this most intimate stowaway that Man, like the whole western political custom, couldn’t resolve. And but the time period “constructed state of affairs,” from which the group took its title, implied that it was potential to seek out one thing like “the northwest passage of the geography of actual life.” And if in his books and movies Man comes again so insistently to his biography, to the faces of his associates and the locations the place he had lived, it’s as a result of he obscurely sensed that this was precisely the place the key of politics lay hidden, the key on which each biography and each revolution couldn’t however run aground. The genuinely political component consists within the clandestinity of personal life, and but, if we attempt to grasp it, it leaves us holding solely the incommunicable, tedious quotidian. It was the political significance of this stowaway—which Aristotle had, with the title zōē, each included in and excluded from the town—that I had begun to analyze in these exact same years. I, too, albeit differently, was in search of the northwest passage of the geography of actual life.

Man didn’t care in any respect about his contemporaries, and he now not anticipated something from them. As he as soon as informed me, for him the issue of the political topic by now boiled all the way down to the choice between homme ou cave (to clarify the that means of this unknown argot time period, he pointed me to a Simonin novel that he appeared keen on, Le cave se rebiffe). I have no idea what he might need considered the “no matter singularity” that years later the Tiqqun group would make—with the title Bloom—the potential topic of the politics to return. In any case, when some years later he met the 2 Juliens—Coupat and Boudart—and Fulvia and Joël, I couldn’t have imagined a closeness and, on the identical time, distance better than the one which separated them from him.

In distinction to Man, who learn narrowly however insistently (within the letter he wrote to me after studying my “Marginal Notes on Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle” he referred to the writers I had cited as “quelques exotiques que j’ignore très regrettablement et [ . . . ] quatre ou cinque Français que je ne veux pas du tout lire”), within the readings of Julien Coupat and his younger comrades you’ll discover the creator of the Zohar mingling with Pierre Clastres, Marx with Jacob Frank, De Martino with René Guénon, Walter Benjamin with Heidegger. And whereas Debord now not hoped for something from his friends—and if one despairs of others one additionally despairs of oneself—Tiqqun had wagered—albeit with all potential wariness—on the frequent man of the 20 th century, the Bloom as they referred to as him, who exactly insofar as he had misplaced all id and all belonging could possibly be able to something, for higher and for worse.

Our lengthy discussions within the locale at 18 rue Saint-Ambroise—a café that they’d left because it was, with its signal Au Vouvray, which nonetheless drew in a couple of passersby by mistake—and on the Verre à pied in Rue Mouffetard have remained as vivid in my reminiscence as people who had animated the evenings on the farmhouse in Montechiarone in Tuscany ten years earlier.

***

On this farmhouse that Ginevra and I—following an unfathomable whim of that spirit that wanders the place it should—rented within the Sienese countryside between 1978 and 1981, we spent evenings with Peppe, Massimo, Antonella, and later, Ruggero and Maries, that I can solely describe as “unforgettable”—even when, as is the case with each really unforgettable factor, there now stays nothing however a cloud of insignificant particulars, as if their more true that means had sunk into the abyss someplace—however the abyss, in heraldry, is the middle of the defend and the unforgettable resembles an empty blazon. We talked about all the things, a passage from Plato or Heidegger, a poem by Caproni or Penna, the colours in certainly one of Ruggero’s portray or anecdotes from associates’ lives, however as in an historic symposium, all the things discovered its title, its delight, and its place. All this will likely be misplaced, is already misplaced, entrusted to the unsure reminiscence of 4 or 5 individuals and shortly to be forgotten solely (a faint echo of it may be discovered within the pages of the seminar on Language and Dying)—however the unforgettable stays, as a result of what’s misplaced is God’s.

***

(What am I doing on this guide? Am I not working the danger, as Ginevra says, of turning my studio into a bit of museum by means of which I lead readers by the hand? Do I not stay too current, whereas I might have appreciated to vanish within the faces of associates and our conferences? To make certain, for me inhabiting meant to expertise these friendships and conferences with the best potential depth. However as an alternative of inhabiting, is it not having that has obtained the higher hand? I imagine I need to run this danger. There’s one factor, although, that I wish to clarify: that I’m an epigone within the literal sense of the phrase, a being that’s generated solely out of others, and that by no means renounces this dependency, dwelling in a steady, comfortable epigenesis).

***

From the window on Vicolo del Giglio you may see solely a roof and a dealing with wall whose plaster, deteriorated in lots of locations, left glimpses of bricks and stones. For years my gaze should have fallen, even distractedly, on that piece of ocher wall burnished by time, which solely I may see. What’s a wall? One thing that guards and protects—the home or the town. Childlike tenderness of Italian cities, nonetheless enclosed inside their very own partitions like a dream that stubbornly seeks shelter from actuality. However a wall doesn’t merely preserve issues out; additionally it is an impediment that you simply can not overcome, the Unsurmountable with which in the end you will need to contend. As each time one comes up in opposition to a boundary, varied methods are potential. A boundary is what separates an inside from an outdoor. We will, then, like Simone Weil, consider a wall as such, in order that it stays thus as much as the top, with no hope of leaving the jail. Or reasonably, like Kant, we would make the boundary the important expertise, which grants us a superbly empty exterior, a type of metaphysical space for storing during which to put the inaccessible Factor in itself. Or as an alternative, just like the land surveyor Ok., we would query and circumvent the borders that separate the within from the skin, the fort from the village, the sky from the earth. And even, just like the painter Apelles within the anecdote associated by Pliny, reduce the borderline with a fair finer line in such a approach that inside and outside change sides. Make the skin inside, as Manganelli would say. In any case, the very last thing to do is bang our heads in opposition to it. The final—in each sense.

Translated from the Italian by Kevin Attell.

From Self-Portrait within the Studio, to be printed this October by Seagull Books.

Giorgio Agamben is certainly one of Italy’s foremost modern thinkers.

Kevin Attell teaches at Cornell College in Ithaca, New York, and is the creator of Giorgio Agamben: Past the Threshold of Deconstruction.