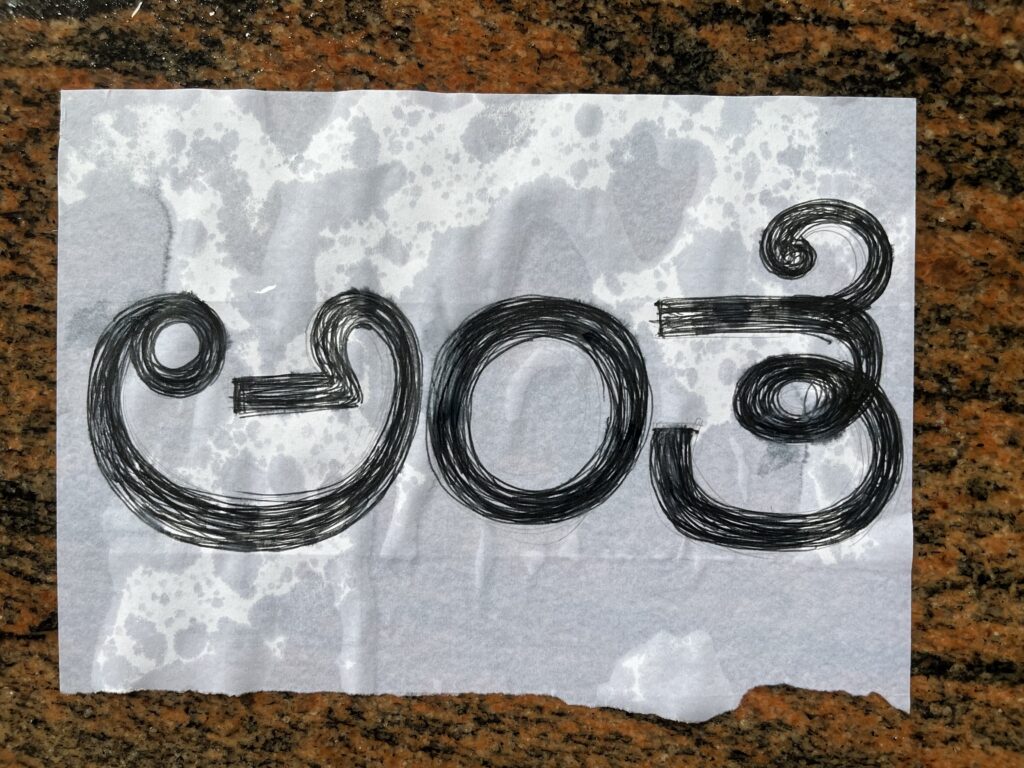

Drawing by Deepa Bhasthi.

Anthe (ಅಂತೆ) is considered one of my favourite phrases within the Kannada language. Considerably meaningless by itself, it provides a lot nuance and emotion when appended to a sentence that we Kannadigas can not keep on a dialog with out utilizing it. Relying on the context and the speaker’s tone, anthe can convey an expression of shock or the understanding that gossip is being shared. It may imply “so it occurred,” “that’s how it’s,” “apparently,” or “it appears.” The latter comes closest to a direct translation, however is a frustratingly easy selection. Anthe will solely ever half-heartedly migrate to English.

Banu Mushtaq, whose brief tales I’ve been translating not too long ago, and whose “Pink Lungi” seems within the Summer season 2024 situation of The Paris Evaluate, employs anthe generously. Mushtaq’s characters use anthe when reporting one thing somebody mentioned verbatim or when guessing how one thing might need occurred. In one other occasion, she makes use of echo phrases with anthe, one other widespread attribute of the Kannada language: one character utters anthe-kanthe to check with rumour. There are additionally a complete lot of ellipses in Mushtaq’s tales … her sentences typically path off … like so … She mixes up her tenses right here and there. It’s all the time deliberate, this nod to the concept time just isn’t linear. The notice that we inhabit totally different time zones and dimensions and dwell in tales inside tales is commonplace in India. These narrative instruments give Mushtaq’s work a way of orality, as if she is sitting throughout from you and telling you the story.

Each time Mushtaq and I do speak in actual life, she is narrating, she is reporting, she is discussing the oppressive political scene in India, she goes again to her youth, laughing about that one time there was a fatwa issued towards her for a narrative—they needed her to cease writing, she informed them to go to hell—she is continually relaying anecdotes and pondering out loud and residing by means of tales. There’s extra anthe in her urgency to convey all the pieces suddenly than I can hope to retailer in my notes.

My favourite perform of the phrase is how its repetition in each different sentence, every in a different way intoned, permits a musicality to slide into every day speech. It offers on a regular basis Kannada its impu, or melody.

Kannada belongs to the Dravidian household of languages native to southern India, and it’s spoken by an estimated fifty to sixty million folks world wide. It’s the official language of the state of Karnataka. Kannada literature has been revealed repeatedly, with none lapse, for fifteen hundred years. Poets have described Sirigannadam, or “rich-Kannada,” as a river of honey, as milk rain, as being as candy as nectar, as reality, as an everlasting language. As previous and celebrated as it’s, Kannada is only one of India’s lots of of languages (estimates fluctuate between 780 and 1,600, along with 1000’s of dialects). An aphorism within the Khari Boli language greatest expresses the nation’s mind-boggling linguistic range: Kos-kos par badle paani, chaar kos par baani, that means that the water in India adjustments each two miles, and language each eight miles.

Mushtaq’s mom tongue just isn’t Kannada, and strictly talking, neither is it mine. Hers is Dakhni, an enchanting mixture of Persian, Dehlavi, Marathi, Kannada, and Telugu that’s typically wrongly referred to as a dialect of Urdu. It’s spoken in elements of southern India predominantly, although not completely, by the Muslim neighborhood. My mom tongue is Havyaka, a dialect that harks again to Outdated Kannada (a parental language that dominated from the ninth to the eleventh century C.E.) and is spoken by a small neighborhood of upper-caste brahmins alongside the Arabian coast in addition to by an identical neighborhood in central Karnataka. (The 2 variations differ and are mutually unintelligible.) Nevertheless, for numerous sociogeographical causes, what I grew up with was a mixture of Kannada varieties widespread to the Mysore area and coastal Mangalore. Each Mushtaq and I dwell in small cities the place we often converse not less than three or 4 languages and numerous dialects. This use of quite a few sociolinguistic programs is, for a really giant variety of Indians, par for the course, and is actually not only a perform of sophistication, caste, training, or mental leanings. I do know a grocer in my city who speaks 13 languages fluently.

Mushtaq’s determination to jot down in Kannada is hardly uncommon as we speak. The second half of the 20th century noticed many eminent multilingual writers select to work in Kannada, the dominant language spoken on the streets, despite the fact that their mom tongues had been Konkani, Telugu, Tamil, Tulu, or others, and so they carried out their skilled lives in English. Such multilingual proficiency is way rarer now—because of the colonial-era Macaulayism that continues to drive India’s English-forward training system, most of us may converse many languages however be proficient solely in English.

Banu Mushtaq sprinkles her Kannada with Dakhni, Urdu, and scant Arabic. Every of those languages can also be additional influenced by native distinctions particular to Bayalu Seeme, a area of Karnataka characterised by open plains, the place she lives. What enriches my translations, I prefer to consider, is a whole immersion within the tradition of the textual content I’m working with. I had a better time translating my first two books, as they had been in languages and from areas I used to be very acquainted with. Mushtaq’s tales are set inside India’s Muslim neighborhood, although her work just isn’t from and for Islamic tradition alone. Nonetheless, her references are a world other than my very own lived experiences. In attempting to bridge the hole in my understanding, I discovered myself reaching for tradition that shared linguistic, social, and aesthetic influences with the milieu of her tales. By some means, this sort of immersion appeared to assist me be higher attuned to the subtleties in her textual content. I used to be launched to the all-consuming world of Pakistani TV dramas, an enormous subculture that overflows with intrigue, suspense, romance, and high-octane drama that thrills most desi hearts. I rediscovered Qawwali music, falling irrevocably again in love with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Parveen, Arooj Aftab, Ali Sethi, their ilk. Alongside my on a regular basis dosage of Kannada-ness, I examine Islam. Reopened my Arabic notes from the teachings I as soon as acquired from a maulvi saheb. Enrolled in a Nastaliq script-writing class through which we studied talaffuz (pronunciation) by way of Hindi movies and poetry. I can not say the place and the way this analysis helped my translation follow. Nevertheless it has enriched my years like something, as we are saying in India.

Any follow of writing and translation on this social terrain can turn out to be very political in a short time. The politics of language in India are, as one may anticipate, a supply of extreme ardour and violence. Whereas consideration to essentially the most distinguished language in any state—Kannada in Karnataka, for example—comes at the price of the prominence, public utilization, and funding for the instruction of a number of others, maybe the best risk to linguistic range throughout India comes from the imposition of Hindi. Spoken principally in elements of northern India, central authorities coverage has traditionally compelled the language upon different states, the place it has typically been violently rejected, particularly within the southern states. These language wars have killed folks, and feelings round imposition of 1 language at the price of others, whether or not Hindi or a regionally dominant language, are all the time simmering beneath the floor. Why translate in any respect, within the face of so many complexities? It is a query we will now not afford to ask. The Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o calls translation “the widespread language of languages.” In India, linguistic hegemony is simply one of many many risks of the homogenizing insurance policies of a far-right-wing-led authorities since 2014. When participating with one other language tradition, one experiences, in studying a brand new phrase or phrase, a glimpse of a distinct world, nonetheless ephemeral.

Within the hierarchy of who will get to translate, who will get to be translated, who will get funding for brand new translations … Kannada doesn’t fare too nicely. Barely a handful of literary translations within the Kannada-English pairing is revealed in a yr. That is miles behind literatures written in, say, Malayalam, Tamil, Bengali, Urdu, or Hindi. To translate in any respect, after which to translate from an underrepresented language, and eventually to translate into English, with all its baggage, is riddled with layers of questions for which there can by no means be easy solutions. I attain again for anthe, attempting to see how complexities can typically stay unresolved. Anthe refuses to let itself be simply carried out of Kannada, which in flip jogs my memory that it’s okay to not have all of the solutions about translation and its politics.

One pleasant facet impact of all of the language cultures we dwell with in India is how typically we toggle between two or three languages when conversing. This reduces language to its primary perform, as a instrument to speak with no matter phrases are inside attain, stripping the necessity for “correct” articulation, throwing out all the foundations. We alternate this pared-down strategy with hyperbole and exaggeration, with repetitions of a phrase for a way of emphasis— “I’ve informed you a thousand occasions,” “small-small,” “round-round,” “two-two occasions …” This interaction of the utilitarian and the embellished, the useful and the decorative, can also be the place I discover the individuality of Kannada once I translate. It is necessary for me to retain these qualities—for example anthe rendered because the insufficient “it appears,” which I’m typically informed just isn’t fairly elegant sufficient English, as a result of carrying these nuances is like talking English with an accent. It reminds the reader that the textual content is from one other tradition. In translation, these expressions stretch the elasticity of the English language. In flip, Kannada beneficial properties one other reader.

Deepa Bhasthi is a author and critic who interprets Kannada-language literature.