{Photograph} by Timmy Straw.

In childhood, books have a odor. Not an precise odor: I’m not speaking in regards to the candy mustiness of a Knopf hardcover circa 1977, or the creaking sawdust odor of a Bantam paperback. I imply that, in childhood, books have the hunch of a odor: the best way, later in life, you would possibly suspect that every factor has a noumenon, a actuality unbiased of our apprehension of it. In childhood, a given ebook’s explicit odor—although it would really odor, like snow, of completely nothing—emits a form of hovering mysterious message: right here is one thing you may give your self as much as, it appears to say; right here is one thing you may give your self over to, and on the identical time by no means fairly attain. On this sense, in childhood, books are extra severe than they’ll ever be once more.

In childhood, you discover a ebook within the library, otherwise you’re handed one—in my case, my studying program circa 1990 was formed by a saturnine and pinchingly beneficiant librarian named Cynthia, who famous our shared inclination towards what I would now name optimistic gloom and gave me, on the age of eight, a kids’s sequence on environmental disasters: Chernobyl, Bhopal, Three Mile Island, Love Canal. It was Cynthia—alarmingly outdated, nimble, with fraying hair, and whose face appeared to shatter when she smiled (a beautiful second in itself, although it was scary to see her face reassemble into its traditional austerity, like watching the breaking of a water glass in reverse on VHS)—it was Cynthia who gave me Robert Cormier’s 1977 YA novel I Am the Cheese.

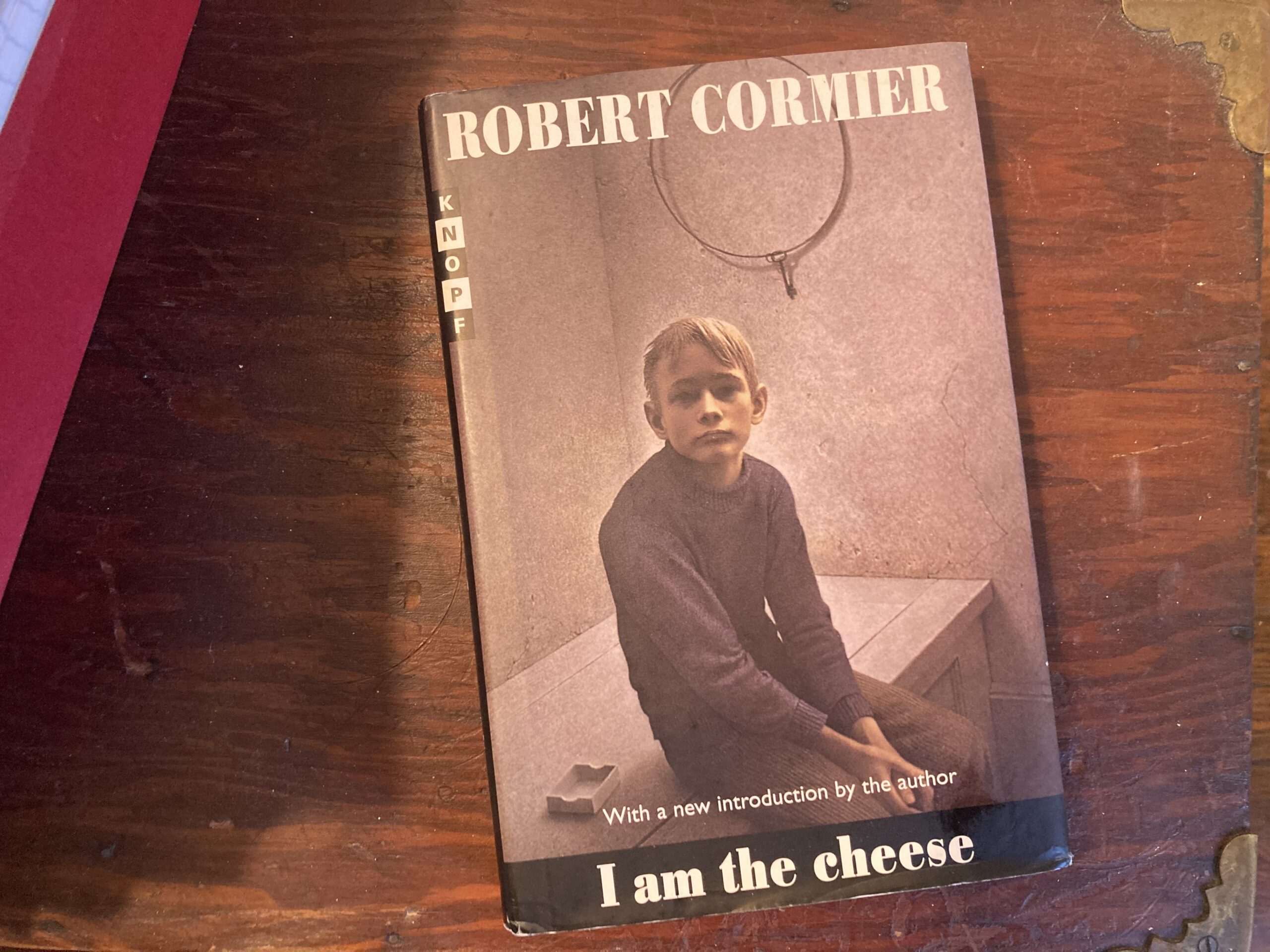

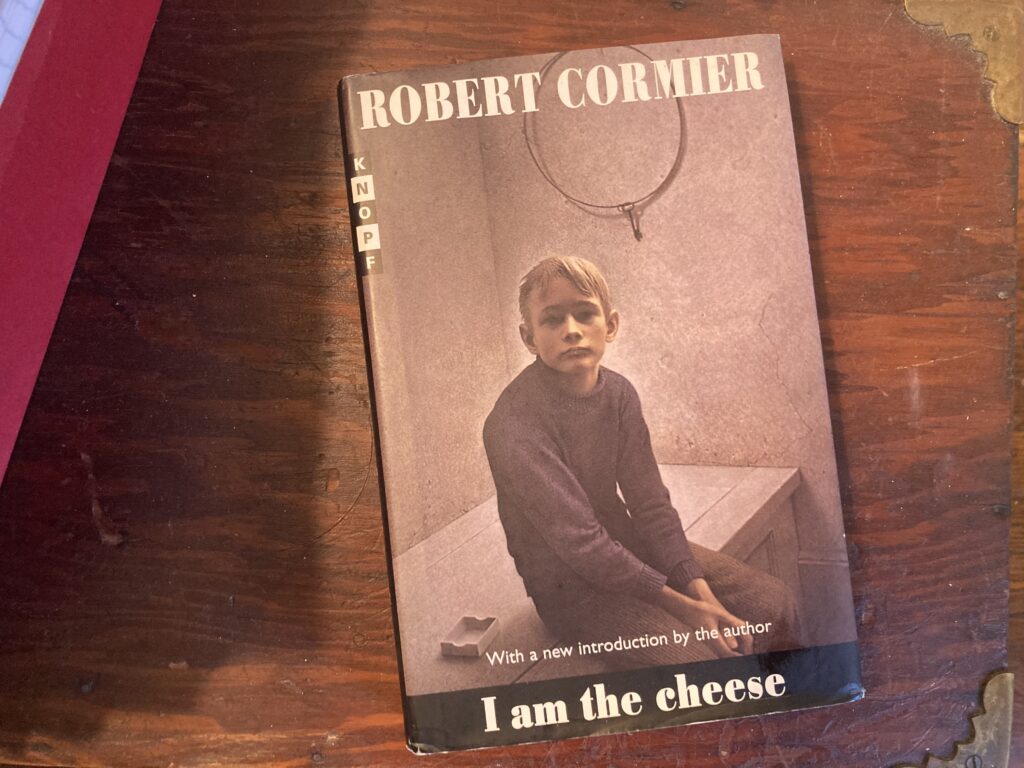

The quilt of the ebook was promising, I noticed. It confirmed a boy, reminiscent of I each thought and wished I used to be, possibly twelve years outdated, with a wistful, reluctant look, massive ears, and sharp elbows; he’s within the grey wash of a jail cell with cracked concrete partitions, a wooden pallet for a mattress, a key (weirdly—why the important thing?) on a peg behind him. And I had a hunch of the ebook’s odor, actually: it was one thing contiguous to the sensation of an fall morning, and to the horizon wanting south, out of city; contiguous, too, to the brackish salt sense of future maturity, of workdays and cash worry, of somebody, sometime, mysteriously desirous to kiss you. In it I sensed some shadow of the long run—as maturity is, for youths, each inevitable and unimaginable; as childhood may be intuited, if you’re a child, because the lengthy shadow of your personal grownup physique solid again onto your youngster current. I Am the Cheese contained a message for me, I felt. I learn the entire thing in a single go, one morning at the back of our Datsun Maxima, headed to the mountains, most likely, the Oregon Cascades, with the ever-present odor of reduce grass and gasoline within the automobile from my father’s landscaping work; I learn the entire thing as if goaded to—whipped on like a canine in a pack of canine behind the musher of the ebook.

It’s a paranoid ebook, and desolate—written, I now perceive, on the finish of the Vietnam Warfare, round Watergate, the grimmer surfaces of world order newly seen within the first hints of Chilly Warfare melt-off—and it was hypnotizing. I dread descriptions of plot, blow-by-blow accounts, however suffice it to say right here: I Am the Cheese entails a household swept up within the nascent witness safety program through the daddy, a small-town-journalist-turned-whistleblower to the violent excesses of presidency corruption. The ebook unfolds by means of the consciousness of the household’s solely youngster, a quiet boy named Adam, and it takes place within the fall, in New England (itself a thrill: me, who had by no means left Oregon besides to go to, as soon as, Fresno). And it’s threaded by means of with references, tightening my ignorant coronary heart to anticipation: references to jazz; to Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel; to petty shoplifting; to the perpetual haunting of the daddy; to shabby motels, diner hamburgers, pay telephones; to conspiracies, particulars, types of love and betrayal organizing like ice crystals simply behind the floor of issues.

It seems, nonetheless, that this anticipation of the center feels fairly totally different in reverse—rereading the ebook this month, I used to be unnerved to find what number of fantasies, wishes, impulses that I had thought my very own have been in reality knowledgeable by it. I noticed that I had, as an example, unconsciously interpreted plenty of troublesome and really actual occasions in my family by means of its fictions; I noticed too that a number of individuals with whom I’ve fallen in love share a glimmer of psychic resemblance to the woman Adam loves. I used to be unnerved to find, in brief, {that a} YA novel could possibly be the supply of a better portion of my instincts and reflexes than appeared in any respect applicable; that it may make fascinating—so fascinating, in reality, as to appear exterior of need—an entire array of emotional tendencies: towards disgrace, melancholy, irreverence, estrangement. As in: hi-ho, the dairy-o, the cheese stands alone.

In childhood, you discover a ebook within the library, otherwise you’re handed one; and how you discover the ebook, and when, and exactly the place you might be if you learn it—these items matter enormously. The standard of the sunshine, the temper at dwelling, the info of fabric circumstance, so normalized as to be each whole and unconscious—in childhood these are as a lot the expertise of the textual content as is the textual content in itself. The ebook and the state of affairs wherein you learn it kind a single climate, and this climate comprises you—it enfolds you, as Walter Benjamin writes within the fragment “Little one studying,” “as secretly, densely, and unceasingly as snow.” It’s simple to assume, then, that there’s some facet of your self nonetheless sitting, mittened and suited up, surprisingly heat, in that very same falling snow; nonetheless turning the pages, even now. And to assume, too, that that is true regardless of how ridiculous, or desolate, or paranoid, or merely competent the ebook—within the mild or darkish of your grownup current—now seems. Or possibly it’s this: that your hunch of the ebook’s odor—its noumenon, if I could—is in some unusual manner sure up in an consciousness of your personal.

Timmy Straw is a poet, musician, and translator. Their poems “Brezhnev” and “Oracle at Canine” seem within the Evaluate‘s Winter 2022 challenge, no. 242.