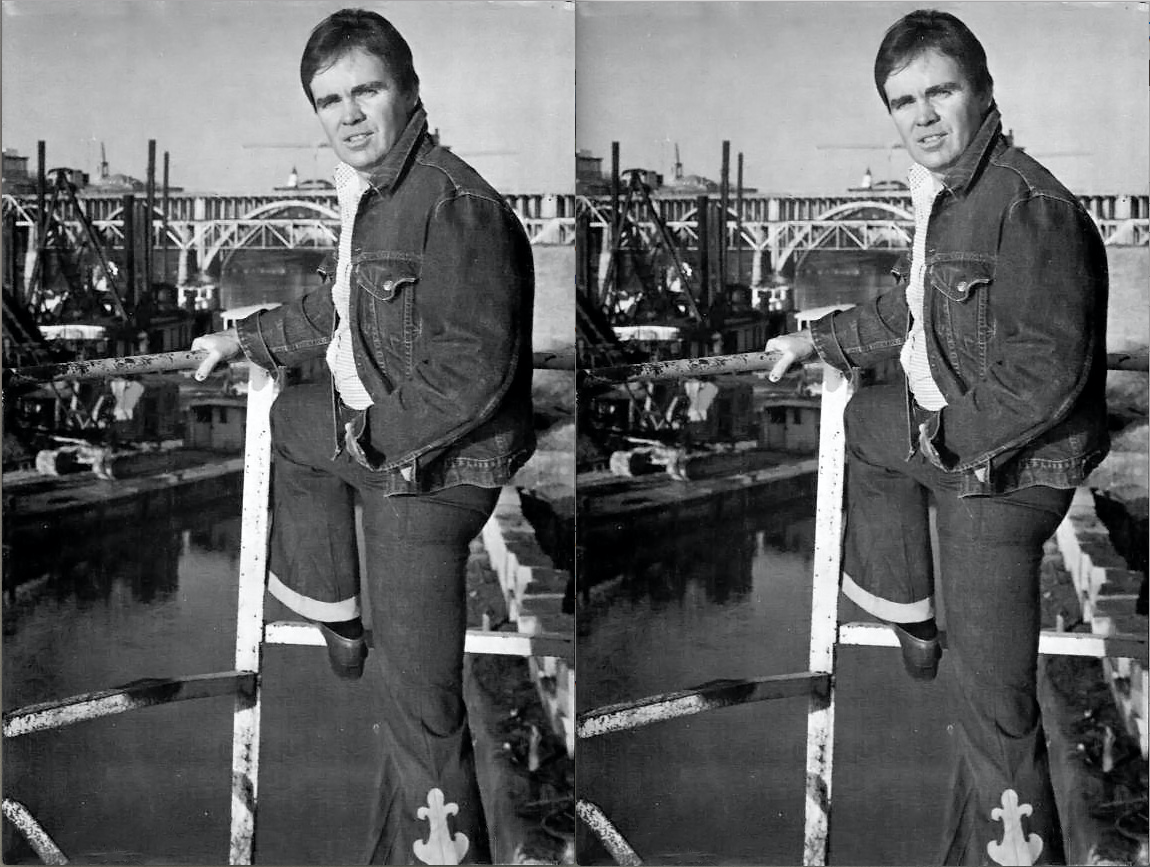

Cormac McCarthy. Public area, by way of Wikimedia Commons. {Photograph} by Dan Moore.

Cormac McCarthy’s work means rather a lot to me, although when I attempt to clarify precisely what, I discover myself unusually stymied; my affinity for him doesn’t make all that a lot sense to me. What connection do I’ve with the landscapes he conjures? What information do I’ve of the form of violence that’s the topic and the material of a lot of his books? What place do I discover in a world that’s, amongst different issues, almost completely masculine, hostile, rife with true desperation? The reply is none—not like with a lot of my studying, I don’t search a mirror in McCarthy’s worldview—and but there’s something in its aesthetic articulation that has all the time resonated with me. (I’ve a curious reminiscence of studying The Highway over my mother’s shoulder after I will need to have been about ten.) I’ve a passage from All The Fairly Horses saved on my desktop, which I’ve revisited usually and ship round from time to time, and which I can not quote in full right here however which ends:

The water was black and heat and he turned within the lake and unfold his arms within the water and the water was so darkish and so silky and he watched throughout the nonetheless black floor to the place she stood on the shore with the horse and he watched the place she stepped from her pooled clothes so pale, so pale, like a chrysalis rising, and walked into the water.

She paused halfway to look again. Standing there trembling within the water and never from the chilly for there was none. Don’t converse to her. Don’t name. When she reached him he held out his hand and he or she took it. She was so pale within the lake she appeared to be burning. Like foxfire in a darkened wooden. That burned chilly. Just like the moon that burned chilly. Her black hair floating on the water about her, falling and floating on the water. She put her different arm about his shoulder and seemed towards the moon within the west don’t converse to her don’t name after which she turned her resist him. Sweeter for the larceny of time and flesh, sweeter for the betrayal. Nesting cranes that stood singlefooted among the many cane on the south shore had pulled their slender beaks from their wingpits to look at. Me quieres? she mentioned. Sure, he mentioned. He mentioned her title. God sure, he mentioned.

The shock of all this tenderness—brutality and tenderness all the time surprisingly twins, by no means removed from one another, by no means balanced. There’s nearly nothing extra transferring than that.

—Sophie Haigney, internet editor

Once I was round fourteen, backpacking in New Mexico’s Cruces Basin Wilderness, not removed from the place I grew up, I used to be made to consider that I used to be going to be attacked by a pack of wolves. The flowery prank trusted recordings of howling performed from a hidden speaker. It could have been merciless, however I used to be silly and city-reared; although wolves as soon as roamed that prime, forested nation, as they did the entire of what’s now the US, we hunted them to close extinction by the thirties, when Cormac McCarthy was born. If Mexican wolves—lobos, these borderland animals that McCarthy described in his novels as “themselves the colour of the desert flooring,” spectral beings that observe “previous ceremonies,” “previous protocols”—had by some means crept up from their extra southern habitat in legion, I’m positive conservation teams would have citizen’s-arrested my celebration for getting too shut. And, most significantly, what would a wolf wish to do with me? Nothing. However I used to be nonetheless terrified. We rimmed a campfire amongst pines and aspen. The flames emitted mild that stopped on the financial institution of a slender close by creek, and the darkness that lay on the opposite facet fashioned a curtain by way of which I briefly believed one thing murderous would emerge.

Inside the prank and earlier than its punchline was, in a means, a small story about McCarthy’s American West, the place complete worlds are destroyed and the open maws left behind overcome us—the place the phantom wolf name creates a black gap. McCarthy wrote figures, like Choose Holden, who had been the genocidal tycoons of that brutal machine and greased its wheels. Others, like Billy Parham, turned its extra oblique, melancholic grist. The operatic violence McCarthy rendered on the web page to present linear form to this cosmic ruination distracts some readers, who assume that gore is the tip to his logic. However he all the time questioned what lay past the desolation. He wrote about love on a regular basis, for one. It by no means actually saved his characters, but it surely allowed their histories to braid into intertwined fates; nonetheless doomed, however bigger than a lonely soul. In his last, beautiful books, particularly in The Passenger, he was exhausted with language whereas wielding it expertly, steering two cursed siblings towards arithmetic, music, and the unconscious in quest of concepts which may provide redemption within the atomic age. They arrive up empty-handed.

There aren’t any wolves in Cruces Basin, after all, and now McCarthy is useless. The areas left by these sorts of endings can not merely be crammed. They’re as an alternative gaping openings that in flip invert and spew outsize, defiant supplies: concern, in addition to tales.

—Elena Saavedra Buckley

The primary time I opened a Cormac McCarthy novel, I used to be twenty-six, dwelling alone by the seashore, unemployed, passing evenings consuming beer with a pair who made camp in a Chevy Suburban on the useless finish of the block earlier than the steps to the boardwalk. The stark actuality of Suttree’s gang of Knoxville misfits revealed a perspective extra outré than I used to be ready for: past bohemian in its societal disdain, and discovering fellowship with the indigent, the prison, the addicted, the merciless, and the deranged. Over the next yr, I learn my means by way of his full oeuvre. Lyrically poignant and ideologically fierce, McCarthy eschewed classification. He had no contemporaries. He wasn’t a part of a motion. And the anecdotes of his life—constructing fireplaces from the stones of James Agee’s childhood residence, plotting to furtively reintroduce wolves to the Arizona desert, altering his title from Charles in order to not be mistaken with the dummy of a well-known ventriloquist of the period—imbue the creator with a near-mythological standing as cabalistic because the tales he penned.

Continuously, his work provides an impression of collaboration with land and historical past: endemic folklores drawn out of America’s bedrock, reflecting the various faces of humanity which have torn it asunder. In Youngster of God, scenes of poverty flip to homicide and necrophilia, urgent past the pale with out ever feeling low cost or contrived. The horrific, frank violence of Blood Meridian—based mostly on reality, and partly allegory for the Vietnam Battle and colonial exploits of that millennium—probes man’s capability for evil. Although he’s greatest recognized for the tangled and grisly, McCarthy was simply as efficient in sentimental romances (The Border Trilogy) and crime thrillers (No Nation for Previous Males). His reward for dialogue is obvious within the humorous and unsettling catechism of The Sundown Restricted, a two-hander play, in addition to his last novels. Towards the tip of his life, he turned evermore to goals, summary math, physics, the unconscious, and the past.

McCarthy, briefly, might do something, and he appeared to view this as a accountability. His rhetoric was daring and sociopolitically pressing, but aligned solely along with his personal imaginative and prescient for the world—one which demanded fixed development and enlargement and awe. From All of the Fairly Horses:

He rode with the solar coppering his face and the purple wind blowing out of the west throughout the night land and the small desert birds flew chittering among the many dry bracken and horse and rider and horse handed on and their lengthy shadows handed in tandem just like the shadow of a single being. Handed and paled into the darkening land, the world to return.

—David Fishkind