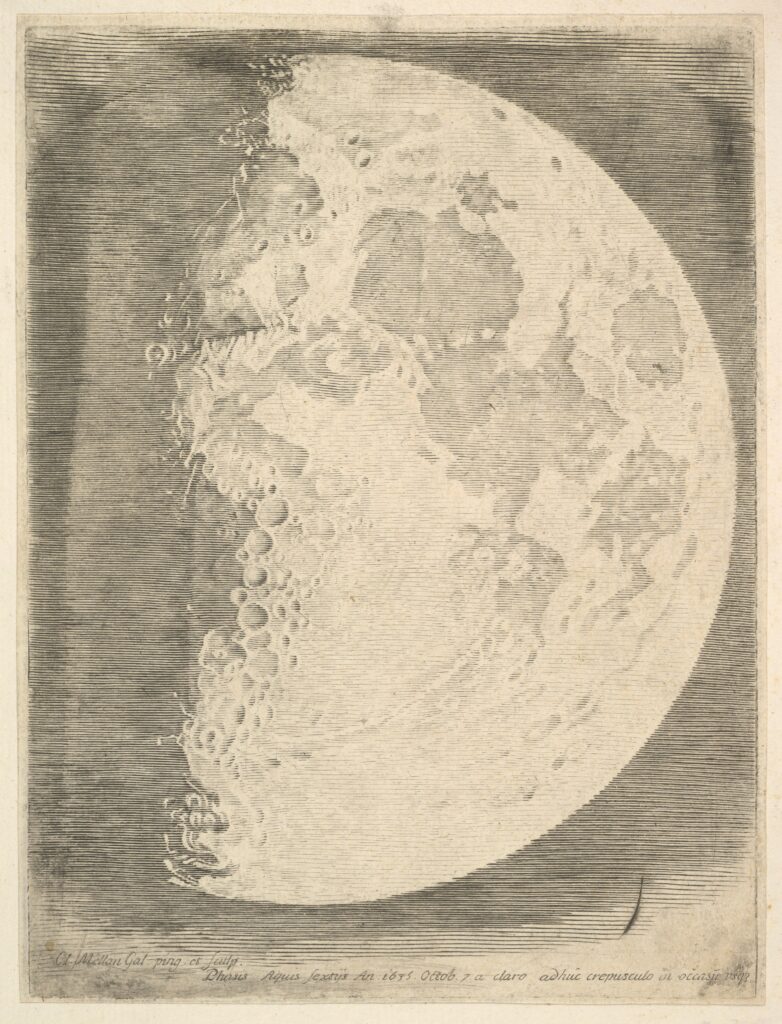

Claude Mellan (French, Abbeville 1598–1688 Paris), The Moon in Its First Quarter, 1635. The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York. From the Elisha Whittelsey Assortment, courtesy of the the Elisha Whittelsey Fund.

I. The World Worlds

It’s most likely not probably the most promising starting to this discuss for me to look at that my topic, like silence, has a approach of disappearing the second you communicate of it. Love, anger, remorse, even boredom—surprise’s antipodes—could entrench themselves in us extra deeply over time, however surprise, I’d enterprise, is at all times already a fugitive affair. Perhaps it’s a matter of developmental psychology; in the course of life, I discover myself changing into a nostalgist of childhood surprise. (Today I really feel it largely in my desires.) Or possibly it’s civilization itself that’s outgrown its surprise years. We begin out with the marvels of the traditional world—the Nice Pyramid of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Colossus of Rhodes—solely to reach, in our disenchanted period, at Surprise Bread. Any approach you slice it, surprise is ever vanishing. Nonetheless, I think the occasional sighting of this endangered have an effect on has one thing to do with why somebody like me continues to jot down poems within the twilight of the Anthropocene. In fact, William Wordsworth mentioned all this extra eloquently and in pentameter verse, too. Perhaps poetry is a faint hint of surprise in linguistic type. By following that hint for the subsequent hour or so, I hope we’ll come a bit nearer to surprise itself.

Let’s start with an early surprise of the Western literary custom. In E-book 18 of the Iliad, the god Hephaestus forges a protect for Achilles, who’s misplaced his armor within the bloody fog of warfare. However as Hephaestus works the protect’s floor, this peculiar blacksmith—being a god, in spite of everything—merely can’t resist making a world, too:

There he made the earth and there the sky and the ocean

and the inexhaustible blazing solar and the moon rounding full

and there the constellations, all that crown the heavens

A bit of creation delusion blossoms amid the slaughter, as Hephaestus hammers not solely Earth however—inside the transient passage of three dactylic hexameters—the totality of the identified cosmos onto the protect as nicely. And he’s solely simply getting warmed up, actually. Over the subsequent 150 strains of the poem, Hephaestus emblazons the protect’s floor with a compact survey of historical civilization, together with the humanities of warfare, regulation, agriculture, animal husbandry, astronomy, music, dance, and so forth. A sensualist at coronary heart, he units this panorama buzzing throughout with Epicurean trivialities: we see “bunches of lustrous grapes in gold, ripening deep purple”; we hear a boy plucking his lyre, “so clear it might break the center with longing”; we even style the savor of “a cup of honeyed, mellow wine.” Not dangerous for a chunk of antiquated army tools. Confronted with such artistry, I can’t assist considering of the protect’s disabled maker as a form of poet, just like the blind Homer himself. Positive sufficient, Hephaestus incorporates a miniature epic into the protect’s pageantry, too, with its personal besieged metropolis, fraught warfare councils, interfering gods, and family members watching anxiously from the ramparts as a tiny surrogate Hector is hauled “via the slaughter by the heels.” No surprise Homer describes the protect as “a world of beautiful immortal work.” It accommodates a complete Iliad and extra inside its gilt compass.

Beguiled by Homer’s artwork, some readers have even tried to reverse engineer actual shields from this literary blueprint over the millennia. In all probability probably the most spectacular instance of all time was fabricated for show at George IV’s coronation banquet by the sculptor, draftsman, and Homer fanatic John Flaxman in 1821. It’s a marvel of nineteenth-century British punctiliousness in low reduction.

The Defend of Achilles designed by John Flaxman and forged by Rundell & Bridge.

Right here we discover bunches of lustrous grapes in gold, a boy along with his lyre, and that cup of honeyed wine—all meticulously accounted for. And but I can’t assist feeling this luminous artifact gives, at finest, solely a low-resolution copy of the Homeric unique. Let’s zoom in for a second on these golden hounds at their masters’ ft to have a better look.

I’m undecided why Homer enumerates the figures on this little tableau with such exactitude amid all of the protect’s armies, crowds, and processions—“and the golden drovers saved the herd in line, / 4 in all, with 9 canines at their heels”—but it surely gives us an ideal alternative to examine Flaxman’s work for high quality management. 4 drovers? Examine. Now let’s depend the canines. (You may assume I’m being persnickety right here, and with good motive, however bear with me just a bit longer.) So the place is that ninth hound? Marianne Moore as soon as famously claimed that “omissions aren’t accidents.” It’s arduous to say whether or not Flaxman’s lacking hound is an omission or an accident, but it surely makes me surprise.

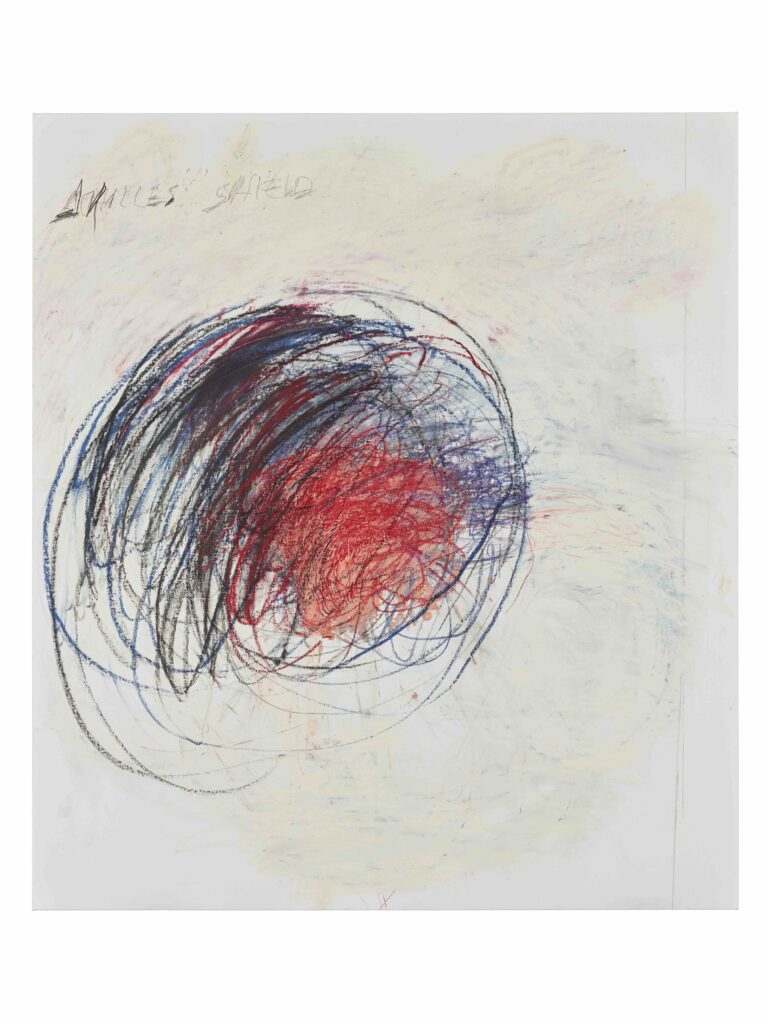

Hear fastidiously, and also you’ll hear the poor beast—“barking, cringing away”—someplace within the vaporous limbo between fiction and actuality. “Paws flickering,” it’s a creaturely cipher for what’s misplaced once we translate the digital into the true. The previous U.S. Military cryptographer and Homer fanatic Cy Twombly illustrates this loss in oil, crayon, and graphite in his postmodern Defend of Achilles a century and a half later.

Defend of Achilles by Cy Twombly, courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Artwork: Present (by trade) of Samuel S. White third and Vera White, 1989, 1989–90–1. Courtesy of the Cy Twombly Basis.

You gained’t discover our lacking hound right here, both—and that’s the entire level of Twombly’s abstraction. All these kinetic scribbles convey Homer’s energeia, or literary power, however additionally they make an absolute hash of the protect’s pictorial imagery. Not even a cryptographer can code a lot world into so small an area. Whether or not you reconstruct it like Flaxman or deconstruct it like Twombly, the protect of Achilles will without end stay an not possible object. It belongs to that wondrous class of issues which can be bigger inside than exterior, like a poem, or an individual, or a world. “The world will not be the mere assortment of the countable or uncountable, acquainted and unfamiliar issues which can be at hand,” writes Martin Heidegger in The Origin of the Work of Artwork, “however neither is it a merely imagined framework added by our illustration to the sum of such given issues. The world worlds.” Homer’s protect isn’t an image of all of the countable or uncountable issues—star techniques, ripening grape clusters, flickering hounds—that populate the world. As Flaxman and Twombly found, it could possibly’t even be pictured in any respect. Nevertheless it worlds.

“Wonderful armor shall be his, armor / that any man on this planet of males will marvel at / via all of the years to come back,” Hephaestus predicts as he hammers the glowing cosmos on his forge. When you have been to survey the readers’ responses to this literary marvel over the millennia—from the nameless commentators of antiquity to moderns like Alexander Pope and G. E. Lessing to undergraduate time period papers in Humanities 101—you’d find yourself with one thing like a short historical past of surprise in Western civilization. Describing the plowmen at work on the protect’s figured floor, Homer himself is the primary amongst mortals to precise surprise at its building:

And the earth churned black behind them, like earth churning,

strong gold because it was—that was the surprise of Hephaestus’ work.

I can’t think about a extra beautiful description of humanity’s passage via the darkish subject of world: “the earth churned black behind them, like earth churning.” However why doesn’t Homer say the protect’s golden floor churned like earth churning? This Möbius strip of a simile is a marvel in its personal proper. Spellbound by Hephaestus’s artistry, we overlook the protect’s a protect within the first place—so we really feel we’re watching soil behave “like” itself. It’s a form of reverse alchemy, the place gold turns into dust, car turns into tenor, and protect turns into world. Generally it appears there’s no escaping surprise earlier than such worlding work. Of the golden ladies depicted within the protect’s marriage ceremony procession, Homer writes, “Every stood moved with surprise.” I’m undecided whether or not we should always envy or pity these embossed figures, without end frozen in transport on the surprise they inhabit.

However there’s a severe glitch within the god’s plans for this “world of beautiful immortal work.” Although Hephaestus prophesies that “any man on this planet of males will marvel” at his craft, not one of the many males within the Iliad—Trojan or Greek—ever marvel on the protect’s building. Achilles’s fellow troopers gained’t even have a look at the god’s radiant work: “none dared / to look straight on the glare, every fighter shrank away.” Solely a blind genius might invent such tragic optics. Homer embeds a gilded cosmos within the midst of the epic for his readers to marvel at via the ages, however the Iliad’s inhabitants stay without end blind to this surprise hidden in plain view. Beholding his present from the gods, even Achilles—the one mortal who scrutinizes the protect’s figured floor—fails to surprise on the sight:

The extra he gazed, the deeper his anger went,

his eyes flashing beneath his eyelids, fierce as hearth—

exulting, holding the god’s shining items in his arms.

Rage (mēnis) is the primary phrase of the Iliad, and we often affiliate it with blindness somewhat than notion: “I used to be blinded, misplaced in my inhuman rage,” says Agamemnon throughout certainly one of his many modifications of coronary heart within the poem. However Homer envisions one thing like a phenomenology of rage on this scene: “The extra he gazed, the deeper his anger went.” For Achilles, anger is greater than have an effect on—it’s an adjunct of notion itself. Solely as soon as he’s “thrilled his coronary heart with wanting arduous / on the armor’s well-wrought magnificence” does he break off his livid gaze. As a substitute of blinding him, rage furnishes this distinctive character with a singular perspective on issues.

Why does Achilles alone rage at this “world of beautiful immortal work”? It could have one thing to do along with his sense of vocation. In E-book 9 of the Iliad, we discover him in his tent, “plucking sturdy and clear on the advantageous lyre” he gained in battle way back, “singing the well-known deeds of combating heroes.” I can’t assist feeling this armchair bard would have made a satisfactory poet in a unique world. (Isn’t each poet a sulky egotist with a hyperactive dying drive, in spite of everything?) However Achilles is born to struggle, to not sing. Something that comes between him and his bloody vocation—together with the “fantastically carved” lyre, “its silver bridge set agency”—should be forged apart for him to comply with this calling. Not even life itself issues extra to him than this grim occupation. “Onerous on the heels of Hector’s dying your dying / should come directly,” his mom warns him, however Achilles solely retorts, “Then let me die directly.” What’s the purpose of residing in case you can now not kill? Achilles doesn’t work to stay, he lives to work—Homer makes use of the phrase ergon, which implies one thing like “labor,” to explain the hero’s exertions on the battlefield—and his enterprise is dying.

Surprise, for the Greeks, led to a really totally different type of vocation. We see this illustrated in a scene from Plato’s Theaetetus, the place Socrates performs his customary function of profession counselor to a youth he’s interrogated to the purpose of utter perplexity:

Theaetetus: By the gods, Socrates, I’m misplaced in surprise after I consider all these items, and typically after I regard them it actually makes my head swim.

Socrates: Plainly Theodorus was not removed from the reality when he guessed what sort of individual you’re. For that is an expertise which is attribute of a thinker, this questioning [thaumazein]: that is the place philosophy begins and nowhere else.

Humorous how Theaetetus should first change into “misplaced in surprise” so as to discover himself. He learns “what sort of individual” he’s—a thinker—from his brush with thaumazein. This beats any aptitude check I took in highschool. For Plato, surprise “is the place philosophy begins and nowhere else.” No surprise, no philosophers. Even Aristotle, who constructed an entire philosophical system from his lover’s quarrel with Plato, agrees on this level. “It’s via surprise that males now start and initially started to philosophize,” he observes within the Metaphysics, “questioning within the first place at apparent perplexities, after which by gradual development elevating questions in regards to the larger issues too, e.g. in regards to the modifications of the moon and of the solar, in regards to the stars and in regards to the origin of the universe.” If this sounds acquainted, it’s as a result of we’ve come full circle, to the origin of the cosmos—the earth, the celebrities, “the inexhaustible blazing solar and the moon rounding full”—that Hephaestus hammered onto the protect’s vibrant circumference within the first place. However we’ve but to contemplate these “larger issues” that type the astronomical rungs on the ladder of Aristotle’s ascent into thaumazein—the moon, the solar, the celebrities, and the origin of the universe. Let’s take the subsequent step in surprise’s philosophical development and look to the moon.

II. Worlds Past

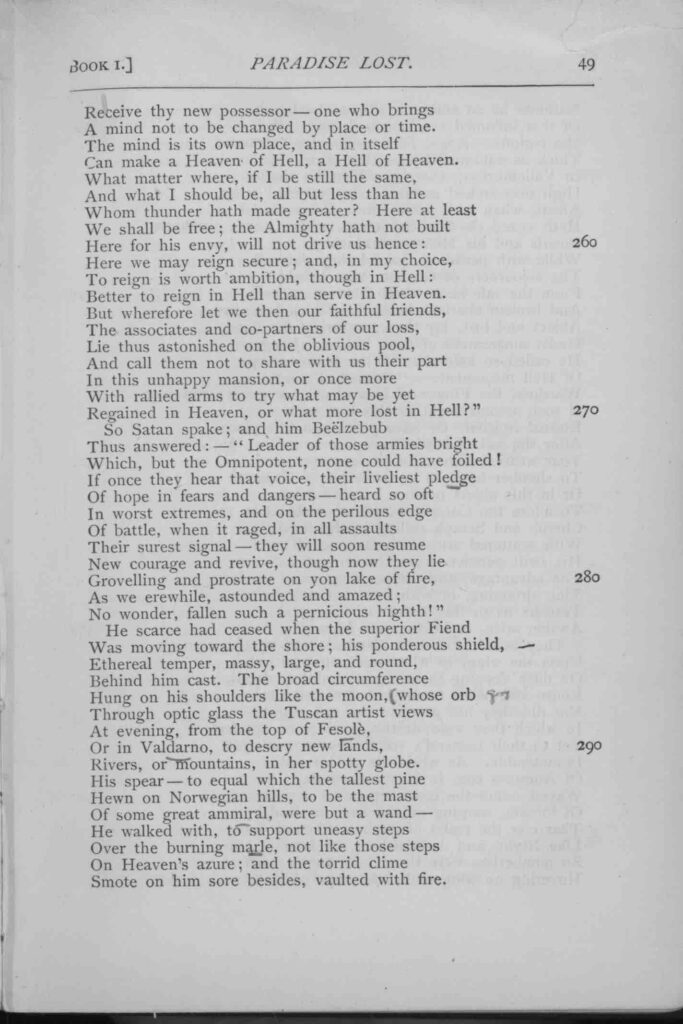

In the end, the moon pops up on just about each poet’s literary horizon. Whether or not you’re a Japanese courtesan, a Yoruban folks singer, or a Conceptualist cosmonaut, it’s as shut because the artwork involves a timeless common motif. However what number of poets ever make the moon really feel new of their artwork? Almost 350 years in the past, John Milton managed to work a nifty little lunar renovation into the epic paraphernalia of Paradise Misplaced, because the irrepressible Devil—after 9 days and nights in free fall from the battlefield of heaven—takes up arms as soon as once more:

His ponderous protect,

Ethereal mood, massy, giant and spherical,

Behind him forged. The broad circumference

Held on his shoulders just like the moon whose orb

Via optic glass the Tuscan artist views

At night from the highest of Fesolè,

Or in Valdarno to descry new lands,

Rivers or mountains in her spotty globe.

Even probably the most pious poet can’t resist a little bit of literary vandalism every now and then. Emblazoning the total moon on Devil’s protect, Milton blots out the classical world of Achilles’s protect—simply as Paradise Misplaced will, he hopes, eclipse the Iliad within the annals of literary historical past sometime. “Massy” but additionally “ethereal [in] mood,” Devil’s protect is one other form of not possible object, or hyperobject. It belongs to that wondrous class of issues that maintain twin citizenship within the realms of the fabric and the best, like a poem, or an angel, or the venerable moon itself. Since antiquity, astronomers had speculated in regards to the moon’s ontology—was it composed of ethereal vapors, or massy just like the earth?—till Milton’s “Tuscan artist” put these theories to the proof with assistance from his “optic glass.” Oddly, we don’t actually see a lot of the moon on Devil’s protect. Superimposed on its “spotty globe,” we discover a portrait of Galileo Galilei—the person in Milton’s moon—who, greater than any poet or insurgent angel, revolutionized our view of the heavens above.

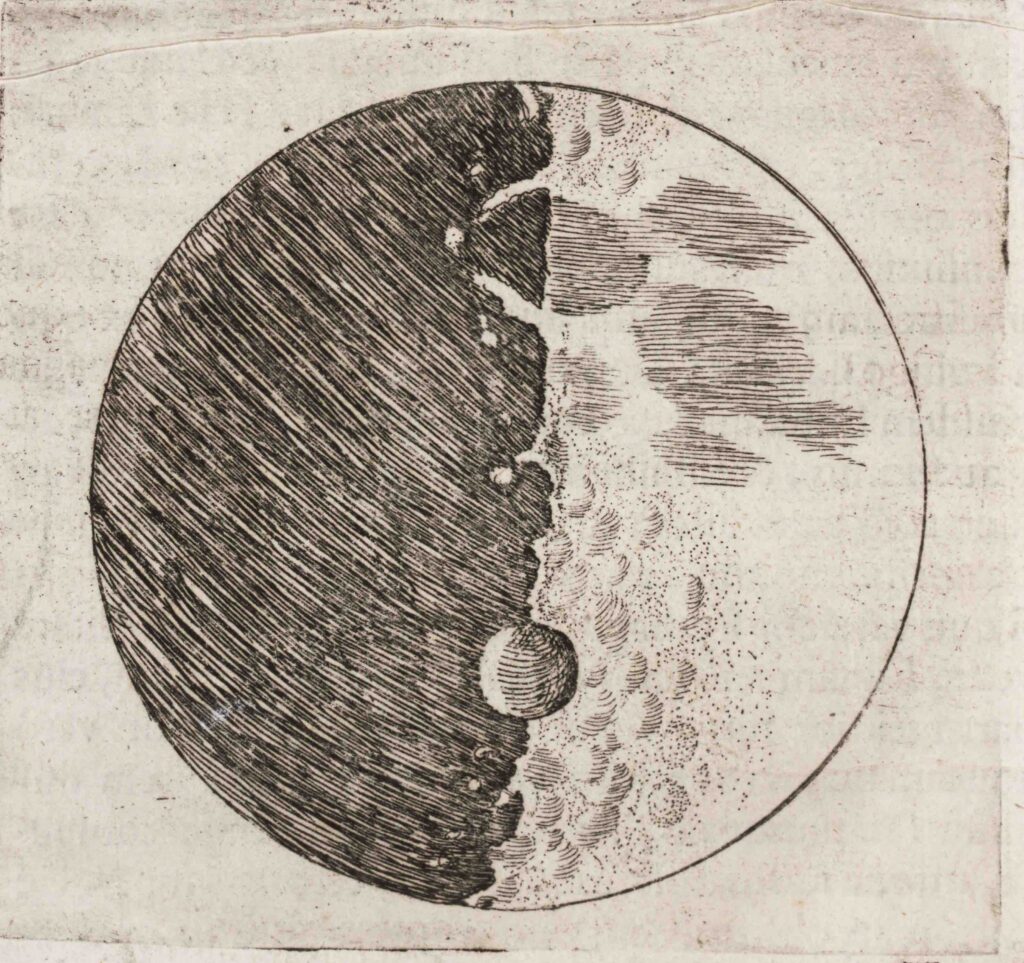

Milton visited Galileo—by then previous, blind, and beneath home arrest—in Florence through the summer time of 1638. (DreamWorks has been sitting on my script of this story for ages.) In his e book The Starry Messenger, Galileo had printed the primary topographical drawings of the moon’s floor to seem within the West practically three a long time earlier.

Galileo’s moon sketch. Courtesy of Linda Corridor Library of Science, Engineering & Know-how.

Peering via his telescope, the Florentine astronomer marveled at a cratered and mountainous terrain that defied expectation:

The floor of the Moon will not be even, clean and completely spherical, as the vast majority of philosophers have conjectured that it and the opposite celestial our bodies are however, quite the opposite, tough and uneven, and lined with cavities and protuberances identical to the face of the Earth, which is rendered numerous by lofty mountains and deep valleys.

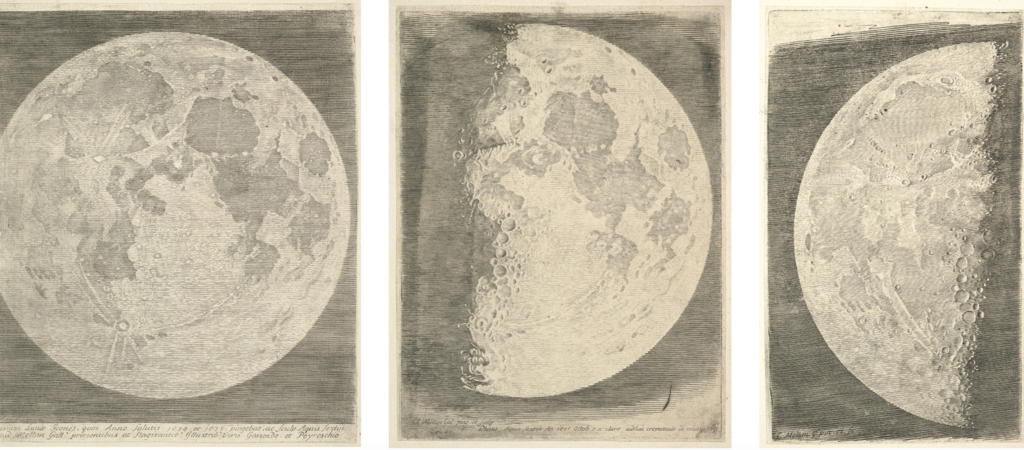

Galileo found that the moon, too, was a world, “identical to” ours. Look carefully at that development of topological nouns ending Milton’s strains, and also you’ll see how the moon got here of age as a world on this interval—from a flat “circumference” to a volumetric “orb” to a mapmaker’s “globe.” In Galileo’s wake, the French engraver Claude Mellan’s moon maps would quickly spotlight the chiaroscuro curvature of the lunar orb.

Three representations of the moon by Claude Mellan, courtesy of The Elisha Whittelsey Assortment, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1960.

By the top of the eighteenth century, the moon had assumed world-like dimensions within the British artist John Russell’s aureate globe.

Moon globe by John Russell.

All this time, Earth was yielding its final clean spots—often known as sleeping beauties—to the epistemological imperium of geography. However now one other “spotty globe” provided “new lands, / Rivers or mountains” to be mapped—and the moon was solely the start.

The moon on Devil’s protect heralds a revolution within the historical past of cosmological surprise. Galileo’s telescope revealed a number of worlds within the heavens above—new moons circling Jupiter, stars by no means earlier than seen by the human eye—all swiftly integrated into blind Milton’s literary imaginative and prescient of the cosmos. Paradise Misplaced levels a common masque of surprise beneath this cover of plural worlds. Awestruck, Adam delivers a Hamletic soliloquy on outer house, which makes of “this earth a spot, a grain, / An atom with the firmament in contrast / And all her numbered stars that appear to roll / Areas incomprehensible.” Milton himself wonders if God may “ordain / His darkish supplies to create extra worlds” from chaos sometime. Devil, too, performs the novice cosmologist, speculating that “house could produce new worlds” for his legions to invade following their expulsion from the dominion of heaven. When you discover Paradise Misplaced gradual going, attempt studying it as science fiction. (Spielberg, what are you ready for?) Nebulous monsters wing their approach via star techniques. Angels and demons alike think about people colonizing different planets. For the primary time in English poetry, we view Earth from outer house—“that globe whose hither facet / With mild from therefore although however mirrored shines”—half cloaked in brightness, half in shadow. I might go on. However amid all this, the archangel Raphael warns Adam—and, consequently, Star Trek aficionados in every single place—to “dream not of different worlds, what creatures there / Dwell in what state, situation or diploma.” Perhaps surprise, just like the moon, has a darkish facet.

Let’s not overlook that probably the most wonderstruck character in Paradise Misplaced additionally occurs to be probably the most fiendish by far. In contrast to livid Achilles, Devil merely can’t cease mooning over all of creation. From the stairway to heaven, he “appears down with surprise” at Earth beneath; as soon as he’s touched down on our planet, he gazes upon Eden “with new surprise”; when he first sees Adam and Eve, he’s overcome by “surprise and will love” them, too. Such vulnerability to surprise, on Devil’s half, is frankly endearing. I, for one, can’t assist feeling sympathy for the poor satan once we final see him—on the conclusion of his ultimate speech to the insurgent angels in hell—nonetheless questioning to the bitter finish:

He stood anticipating

Their common shout and excessive applause

To fill his ear when cóntrary he hears

On all sides from innumerable tongues

A dismal common hiss, the sound

Of public scorn. He puzzled however not lengthy

Had leisure, wond’ring at himself now extra:

His visage drawn he felt to sharp and spare,

His arms clung to his ribs, his legs entwining

One another until supplanted down he fell

A monstrous serpent on his stomach susceptible

I’ve felt this manner after poetry readings myself typically. (Isn’t each poet a narcissistic angel in reptilian type, in spite of everything?) Devil’s final object of surprise in Paradise Misplaced isn’t a newly found planet, or humankind, however “himself,” reworked right into a serpent. You’d anticipate Devil to really feel horror at this grotesque Ovidian metamorphosis—his skull warping hideously, his arms fusing into his torso, his legs corkscrewing right into a scaly tail—however this antihero’s wondrous journey via the cosmos ends the place it started, in a failure to see himself for what he actually is. Perhaps dreaming an excessive amount of of worlds past attain could make a monster of you.

Worlds swim via Paradise Misplaced like bubbles in a glass of champagne, however Milton cautions us to not lose sight of ourselves on this teeming universe. Who’s extra blind to our world than the astronomer squinting into his telescope’s eyepiece? “They will foresee a future eclipse of the solar,” writes Augustine in his Confessions, “however [they] don’t understand their very own eclipse within the current.” I think Milton had this type of interior eclipse in thoughts when he described Devil’s dusky radiance following the archangel’s fall from heaven:

His type had not but misplaced

All her unique brightness nor appeared

Lower than archangel ruined and th’ extra

Of glory obscured, as when the solar, new ris’n,

Seems via the horizontal misty air

Shorn of his beams or from behind the moon

In dim eclipse disastrous twilight sheds

On half the nations and with concern of change

Perplexes monarchs. Darkened so, but shone

Above all of them th’ archangel

Milton’s selenographic protect could promote Galileo’s discoveries, however its spotty globe additionally reminds us that Lucifer—the erstwhile “bringer of sunshine”—is, in fact, eclipse personified: “Darkened so, but shone / Above all of them th’ archangel.” Nothing discloses the darkish facet of surprise like an eclipse. I as soon as noticed one, via a chunk of welder’s glass, in a derelict park on the opposite facet of the world. Even the crows appeared perplexed by its disastrous twilight. There was an uncanny chill, as if a fridge door had swung open inside me. However the surprise of all of it wasn’t that the solar had been blotted out overhead. What stopped my breath was the gradual silhouette of one other world gliding into view.

III. Worlds Inside

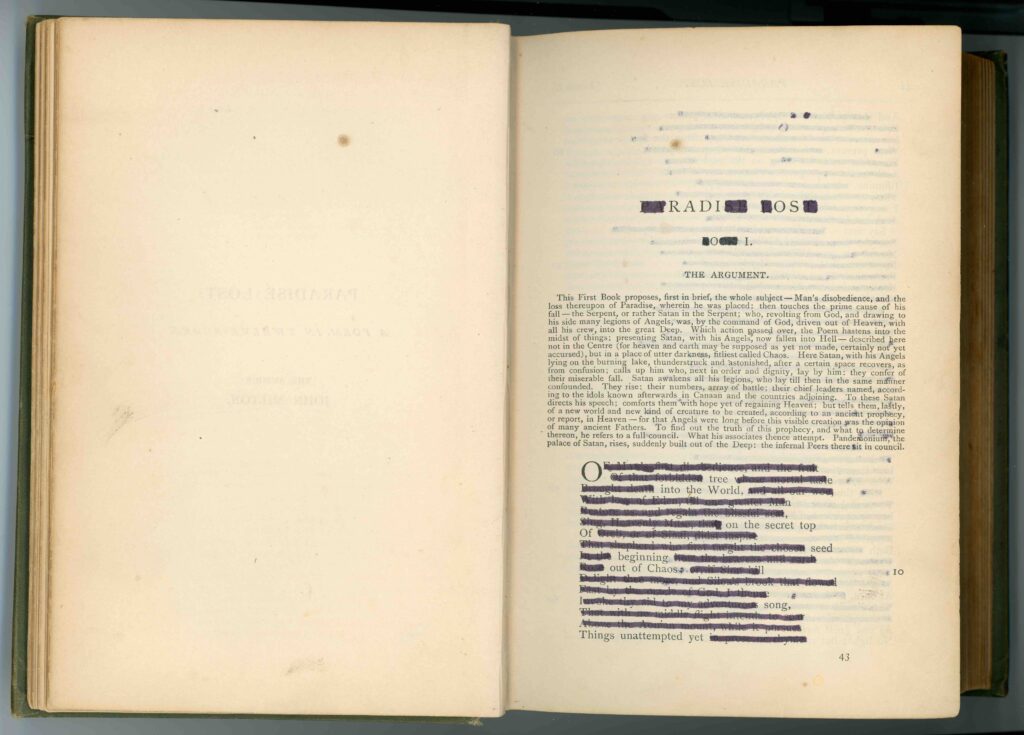

Three centuries after Paradise Misplaced first lit up the Western literary firmament, an American poet, cookbook writer, and marijuana fanatic named Ronald Johnson bought an 1892 version of Milton’s poem in a Seattle bookshop—and promptly started to black out a lot of the textual content from its pages.

Picture courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Assortment, Kenneth Spencer Analysis Library, College of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Property of Ronald Johnson.

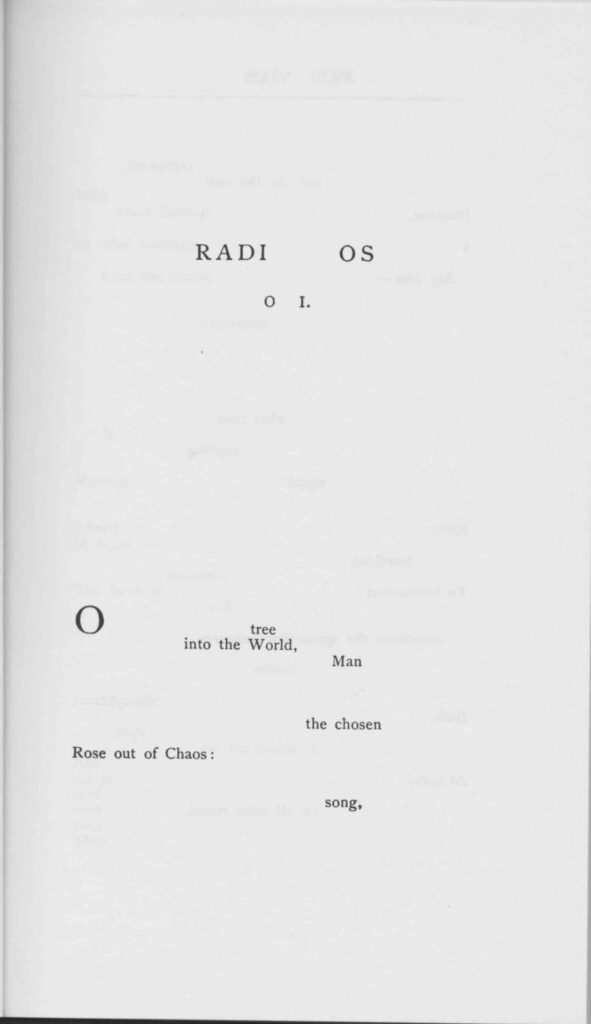

Why would anybody so meticulously deface an already outdated copy of the venerable Puritan epic? “I bought about midway via it, form of as a joke,” Johnson later defined in an interview, like a sheepish delinquent caught spray-painting a cathedral. “However I made a decision you don’t tamper with Milton to be humorous. You must be severe.” What started as a bit joke at Milton’s expense developed right into a postmodernist masterpiece of literary eclipse in its personal proper. Blot out the primary and final two letters of paradise, and you’ve got radi. Lose the primary and final letters of misplaced, and you’ve got os. Even the title of the poem Johnson common from this process—Radi Os—is ordained solely from Milton’s darkish supplies.

Earlier than publishing this literary curio, Johnson scrupulously whitewashed the epic he’d defaced, yielding a photographic destructive of his poetic eclipse:

Picture courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Assortment, Kenneth Spencer Analysis Library, College of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Property of Ronald Johnson.

No one wrote Radi Os. The poem was wondrously erased into existence. Its writer’s phrases are nowhere to be discovered on this work, and but—like Milton’s Creator—he’s in every single place.

“There’s one other world,” the French poet Paul Éluard as soon as mentioned, “however it’s inside this one.” I believe Johnson would gently amend this to say there are different worlds, however they’re inside this one. Turning the astronomical theater of Paradise Misplaced inside out, Johnson investigates the plurality of worlds inside: “worlds, / That each in him and all issues, / drive / deepest.” A bit of textual puzzle from ARK, the cosmological epic Johnson labored over for twenty years, illustrates the wondrous multiplication of interior worlds all through this poet’s work:

earthearthearth

earthearthearth

earthearthearth

The literary critic Stephanie Burt has deciphered the key messages embedded on this triple-decker concrete poem. Earth, earth, earth. Ear, the artwork fireside. Hear the artwork, hear the artwork. Sampling a jeremiad from the King James Bible—“O earth, earth, earth, hear the phrase of the Lord”—Johnson composes a manifold matrix of worlds (and hearts). It’s one factor to register the verse in universe and one other solely to assemble a poetics of the multiverse. The erasurist’s determination to not delete the s that pluralizes his e book’s title makes worlds of this distinction. Radi Os isn’t a radio; it’s an orchestra of radios. Nicely, that’s not fairly proper. See that caesura fracturing the poem’s title? An imaginary variety of damaged “radi os” hums and buzzes inside this literary hyperobject. One radio could tune right into a single frequency at a time, however a refrain of damaged radios can broadcast every little thing from an infernal racket to the music of the spheres abruptly. “You don’t tamper with Milton to be humorous,” our holy idiot could attest, however for all its radical theology, Radi Os is, in the long run, a divine musical comedy.

Hear fastidiously, and also you’ll hear a marvelously cracked piece of postmodern music taking part in backstage of Johnson’s literary erasure. At a celebration along with his college students one evening—so the story goes—the poet first heard a recording of Baroque Variations, by the composer Lukas Foss. At one level within the work, a xylophone spells out Johann Sebastian Bach in Morse code. Elsewhere, a extremely skilled musician smashes a bottle with a hammer. Johnson’s numerous enthusiasms should have lined up properly that night, as a result of he embarked upon the “solitary quest within the cloud chamber” that may change into Radi Os the very subsequent day. Within the dedicatory be aware to his e book, Johnson quotes Foss’s liner notes for Variation I—on a larghetto by Handel—as a type of key to his personal work:

Teams of devices play the Larghetto however hold submerging into inaudibility (somewhat than pausing). Handel’s notes are at all times current however usually inaudible. The inaudible moments depart holes in Handel’s music (I composed the holes). The perforated Handel is performed by totally different teams of the orchestra in three totally different keys at one level, in 4 totally different speeds at one other.

Handel’s larghetto, from the Concerto Grosso, op. 6, no. 12, could very nicely be probably the most stunning melody the composer ever wrote. It’s straightforward sufficient to search out on-line, in case you’d like to listen to the “at all times current however usually inaudible” unique music behind Foss’s détourned Variation I someday. Then hearken to the Foss, and also you’ll expertise the otherworldly great thing about Handel beneath eclipse. It’s arduous to not hear damaged radios trying to find a classical music broadcast on this perforated larghetto’s eerie harmonics and bursts of sonority. When you discover Radi Os gradual going, attempt studying it because the libretto for a post-structuralist house opera—lyrics erased by Johnson, rating perforated by Foss.

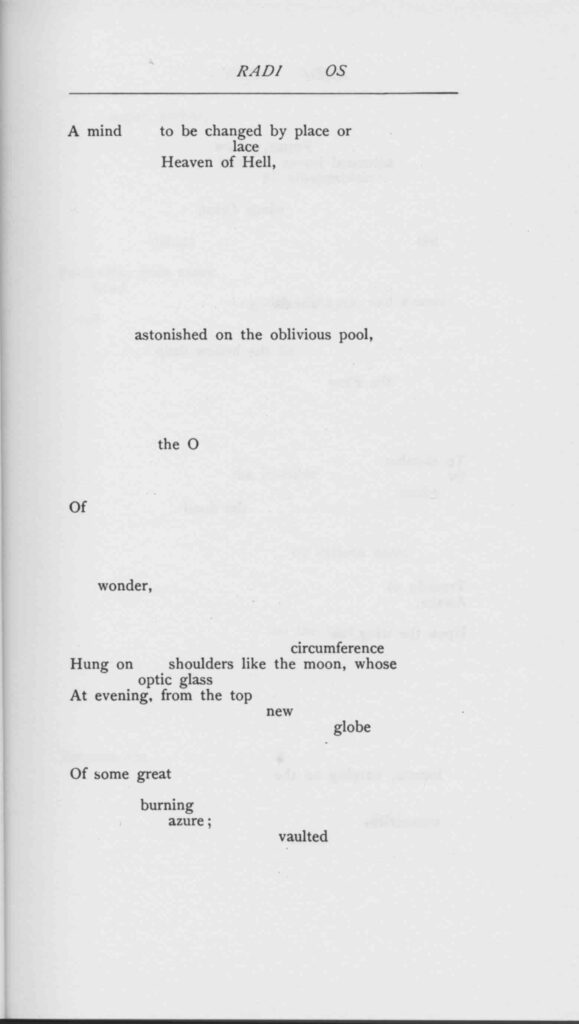

The surprise of variations—in music, in poetry, in evolutionary biology, and elsewhere—is how one variation begets one other, although you by no means know what you’ll beget. Perforating Paradise Misplaced, Johnson produced a literary variation on Foss’s musical variation on a Baroque artist who composed dozens of variations of his personal—together with Hephaestus’s favourite, “The Harmonious Blacksmith.” To see how Radi Os makes doable even additional variations on itself, let’s have a look at the unique passage within the 1892 version of Paradise Misplaced on the web page the place Devil’s protect first seems.

Picture courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Assortment, Kenneth Spencer Analysis Library, College of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Property of Ronald Johnson.

What if someone aside from Johnson—say, a younger lady in rural New England on a snowy evening way back—have been to compose her personal holes on this darkish materials?

time

Can

thunder

Right here

Right here in my

sad mansion

however

that voice

Of

hearth

scarce ceased

the

Ethereal

artist

in her globe

Of

marle steps

On and

on

It’s hardly “As a result of I couldn’t cease for Demise,” however you get the thought. There are innumerable poems encrypted within the “harmonious numbers” of Paradise Misplaced. I even hear echoes of the sadly underrated poet, Star Trek aficionado, and Ronald Johnson fanatic Srikanth Reddy on this literary cloud chamber.

The thoughts is

a

matter

my

pals

of

voice

the edge

Of it

shifting

like

glass

in

Rivers

however

burning

I might do that without end, and that’s precisely the purpose. You would, too. I think that’s why Johnson breaks off his personal work at E-book 4 of Paradise Misplaced, leaving practically seven thousand strains of pristine Miltonic pentameters for others to cross out sometime. “Radi Os form of wrote itself,” mentioned the writer of this unfinished erasure. “I believe it ended when it wanted to finish, and I didn’t want so as to add the remainder.” An open-ended variation on Milton’s track, Radi Os invitations us to “add the remainder.” And why cease at Paradise Misplaced, for that matter? Compose your individual holes in any e book—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Structure of the US of America, The Unsignificant—and also you’ll unearth a manifold matrix of worlds inside.

A literary multiverse, Radi Os is riddled with cosmological wormholes, theological rabbit holes, and typographical holes. From the “O tree,” a slant rhyme for poetry that opens the work, to the “O for / The Apocalypse” that trumpets the poem’s closing revelations, Johnson makes us see the gap in entire and listen to the gap in holy. There’s a gap in surprise, too, although I’d by no means tumbled via it till I got here throughout the next web page in Radi Os:

Picture courtesy of the Ronald Johnson Assortment, Kenneth Spencer Analysis Library, College of Kansas. Used with permission of the Literary Property of Ronald Johnson.

The primary time I learn this passage, I had no thought what lay behind it. However that floating little phrase—“the O / Of / surprise”—saved looping round in my head, so I dug up an previous copy of Paradise Misplaced to learn the Miltonic unique and was wonderstruck. Virtually three thousand years in the past, a blind Greek poet pictured the world on an historical protect. Two and a half millennia later, the moon spied via an optic glass eclipsed Homer’s world in a theological poem of Reformation England. In my very own lifetime—I used to be 4, astronauts had set foot on the moon’s floor just a few years earlier—a little-known American poet erased Milton’s spotty globe all the way in which all the way down to a wondrous O. World, moon, O. The phrase for when issues line up on this approach is syzygy. The microscopic linkage of chromosomes vital for copy in our species is one instance. An eclipse—when three celestial our bodies line up in astronomical house—is one other. The phrase syzygy is itself a syzygy, which just about makes me consider in clever design so far as language is anxious. Learn aloud its sequence of three similar vowels lined up in a row—y, y, y—and also you’ll hear humankind grappling with the thriller of causation. Let’s not overlook that linked chain of o’s in “the O / Of / surprise,” both. It’s a syzygy, too. Why, why, why? Oh, oh, oh. All of us stay that track.

So many pictures flicker via this O in Radi Os—a full moon, a ghostly protect, a gap in a web page from a timeworn version of Paradise Misplaced—however I at all times return to a mouth open in surprise. Once we see golden acrobats turning handsprings on an historical protect, or when the mountains of the moon first swim into focus via a telescope’s eyepiece, we are saying “O,” hardly conscious that our lips are assuming the form of the signifier itself. The “O” of surprise, Johnson exhibits us, is the o in surprise. I can’t consider another phrase the place our writing system and the morphology of human speech enter into such wondrous alignment. However the mouth varieties an O in arousal, and in starvation, and in dying’s terminal rictus, too: “Thy mouth was open,” George Herbert says to Demise personified, “however thou couldst not sing.” There’s no such factor as pure or easy surprise. When thaumazein forces our lips into an O, all these historical drives—from Eros to Thanatos—transfer via us as nicely. The artwork of poetry historically originates on this inexhaustible, sonorous “O.” O muse, O Lord, O my love, O late capitalism, O etcetera—the O that Johnson plucks out of surprise invokes countless poetic variation. With all due respect to Plato and Aristotle, philosophy isn’t the one vocation that springs from thaumazein. When you look carefully on the O of surprise, you’ll see a poem starting there, too.

Srikanth Reddy is the poetry editor at The Paris Evaluate. This lecture can be printed in Reddy’s The Unsignificant: Three Talks on Poetry and Photos, forthcoming from Wave Books in September.