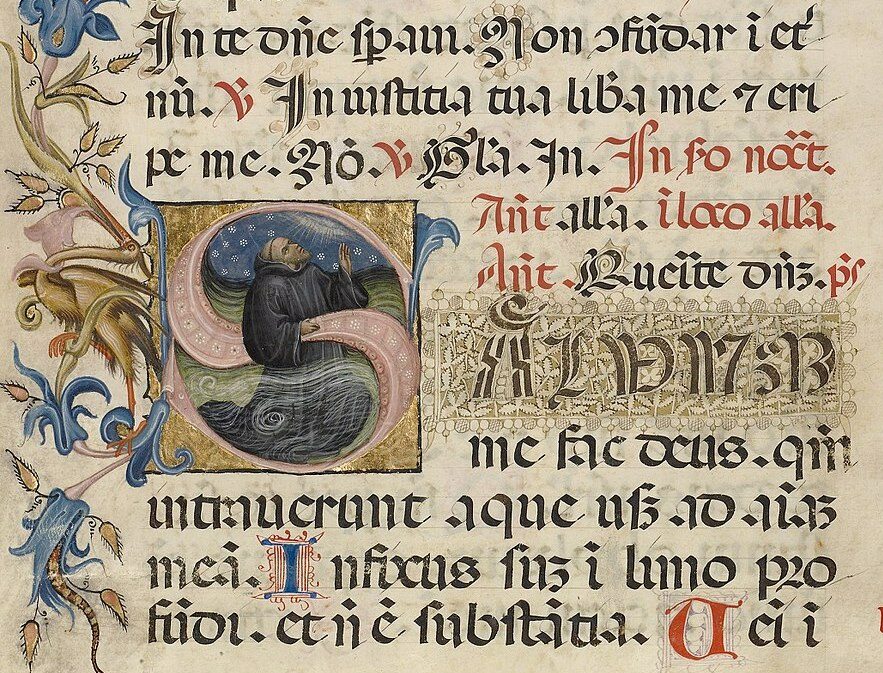

Preliminary S: A Monk Praying within the Water, Getty Middle. Public area, by way of Wikimedia Commons.

We don’t learn the Bible as it’s meant to be learn. Theology all the time dangers main us astray by elaborating its personal discourse, with the biblical texts merely as some extent of departure. The presence of poetry within the Bible is the important thing to a extra pertinent and extra devoted studying.

There are a lot of poems discovered within the Bible. We all know this, vaguely and with out giving it an excessive amount of thought, however shouldn’t we be quite astonished by the position of poetry in a group of books with such a urgent and salutary Phrase to precise? And shouldn’t we ask ourselves if the presence of this writing—a lot extra self-conscious and desirous than is prose of a type it will probably make vibrate—impacts the biblical “message” and adjustments its nature?

It’s unsurprising that the Psalms are poems, given their liturgical function and the abyss of particular person and collective emotion that they discover. On the coronary heart of the Bible and but additionally other than it, they lay out, we’d suppose, for each the person and the neighborhood, the lived expertise of faith that different biblical books have the duty of defining. We are able to settle for the Music of Songs as a love poem, Jeremiah’s Lamentations as a sequence of elegies, Job as a verse drama, and we uncover with out an excessive amount of shock a substantial variety of poems within the historic books: the music of Moses and Miriam, for instance, in Exodus 15; the canticle of Deborah and Barak in Judges 5; the lament of David for Saul and Jonathan in 2 Samuel 1. And but once we take into consideration the presence of all these poetic books in a piece wherein we anticipate finding doctrines, and in regards to the flip to poetry in so lots of the historic books of the Bible, it provides us cause to suppose once more. And the way ought to we react to Proverbs, wherein knowledge itself is taught in a poetic type? Or to the prophetic books, the place poetry is sovereign, the place warnings of the best urgency, for us in addition to for the writers’ contemporaries, come forth in verse?

Isn’t this curious? And poetry seems from the start. Within the second chapter of Genesis (verse 23), Adam welcomes the creation of lady on this method:

Right here finally the bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh.

This one shall be referred to as lady, for she was drawn forth from man.

These are the very first human phrases reported; it’s tempting and maybe reliable to attract some conclusions. By this level Adam has already named the animals, however the writer solely signifies this, with out recording the spoken phrases; on the planet of the start, from which the writer is aware of himself in addition to his readers to be excluded, he in all probability acknowledged that there will need to have existed an intimate relationship between language and the true, between phrases and issues, that we’re incapable of regaining. However when Adam does converse for the primary time, he’s given an “Edenic” language, one which our fallen languages can nonetheless attain in sure moments: thus Adam actually attracts lady, ’ishah, from man, ’ish. Hebrew, because of the pleasure it takes in wordplay—within the ludic and deeply severe harmonies between the sounds of phrases and the beings, objects, concepts, and feelings to which they open themselves—is a language notably and providentially skillful at suggesting what can be a cordial relation between our language and our world, and a significant relation among the many presences of the true. It’s skillful in affirming the gravity of the lightest among the many figures of rhetoric: the pun. Most significantly, as quickly as the primary man opens his mouth, he speaks in verse. Did the writer suppose that on the planet of primitive surprise language was naturally poetic? Is that this why Adam, instantly after consuming the forbidden fruit, responds to God in prose: “I heard your steps within the backyard, and I used to be afraid as a result of I used to be bare, and I hid myself” (Genesis 3:10)? We can not know, however that first temporary, spontaneous poem of Adam, which we appear to listen to from so far-off and from so shut, solicits our consideration and requires our thought. If language earlier than the Fall was poetic, or produced poems at moments charged with which means, does poetry characterize for us the apogee of our fallen talking—its starting and its finish, its nostalgia and its hope?

In paging by way of Genesis, a ebook of historical past and never a group of poetry, we encounter a powerful variety of poems. It’s in poetry that God provides the regulation on homicide and its punishment (Genesis 9:6), that Rebecca’s household blesses her (24:60), that Isaac prophesies the way forward for Esau (27:39–40), and that Jacob blesses the twelve tribes of Israel (49:2–27). Given the occasional issue of figuring out which passages are in verse, it could be that others will likely be found. The Bible de Jérusalem (I’m studying from a 2009 version) presents God as talking in poetry a number of instances within the first three chapters, starting with the creation of man, because the Phrase of God provides delivery to the one creature endowed with speech:

God created man in his picture,

within the picture of God he created him,

man and lady he created them.

In approaching the Bible’s starting, we should usually change our listening, our rhythm, our mode of consideration and of being, as a way to perceive and obtain a special language.

There are fewer poems within the New Testomony, however they provide much more meals for thought. The Gospel of Luke introduces, from its first chapters, three poems: the canticles of Mary, Zachariah, and Simeon. Thus the Savior’s life begins underneath the signal of poetry. The ebook of Revelation, on the finish of the Bible, accommodates extra canticles, in addition to lamentations on Babylon, in poetry that appeals to the visionary creativeness. Within the identify of Christianity, it returns to the extravagant poetry of the prophets. The primary letter of John develops its thought with such felicity of rhythmic phrasing and close-crafted type that the Jerusalem Bible interprets it fully in verse. These identical translators have Paul’s letter to the Romans start and finish in verse, thus utilizing poetry to border a doctrinal exposition animated by an infected however in precept “prosaic” strategy of reflection, evaluation, and synthesis.

Jesus himself appears at sure moments to talk in verse, as within the Beatitudes (Matthew 5, Luke 6) and the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6, Luke 11). Within the Jerusalem Bible, the Gospel of John, which begins with an extended poem and wherein John the Baptist on two events speaks in verse (1:30, 3:27–30), means that Jesus the trainer—or quite, the divine educator—addressed his listeners most frequently in poetry.

It’s true that the border between verse and a cadenced prose is just not simple to find out in both the Hebrew of the Previous Testomony or the Greek of the New: translators choose it in another way. It could even be that the poems spoken by Jacob, Simeon, and plenty of others come not from them however from the authors of the books wherein they seem. The outcome is identical. We discover ourselves continuously within the presence of writings that invite us into the enjoyment of phrases, right into a well-shaped language, in a type that calls for from us the eye that we give to poetry and awakens us to expectation.

***

Sure students of the Bible have lengthy identified that the poetry is just not there merely so as to add a touch of the Aristocracy, or sublimity, or emotive pressure to what the writer might have stated in prose. They realized from literary critics what the critics had realized from poets: poetry is in itself a mind-set and of imagining the world; it discovers with precision what it needed to say solely by saying it; the which means of a poem awaits us in its method of being, and which means within the customary sense of the phrase is just not what’s most vital about it.

Ought to we not ask ourselves if the presence of so many poems adjustments not solely the best way wherein the Bible speaks to us, but additionally the type of message, announcement, or name that it conveys? How should religion understand biblical speech? What does this continuous flip to poetry suggest in regards to the very nature of Christianity?

We are able to begin to answer these questions by giving some thought to how we often learn poetry. We don’t paraphrase poems, extracting a which means and leaving apart the redundant type. It’s the very being itself of the poem that issues, the sounds and the rhythms that animate it like a dwelling factor, the relations that the phrases sew amongst themselves by way of their reminiscence and their historical past, and the connotations that they disseminate.

Nevertheless, whereas we learn a poem of Keats, or of Baudelaire or Ronsard, on this method, we simply overlook our customary consideration to the lifetime of the poetic phrase when studying, for instance, a Psalm, from which we need to draw a instructing, a lesson. We have to be reminded of two well-known pensées of Pascal: “Totally different preparations of phrases make totally different meanings, and totally different preparations of meanings produce totally different results”; “The identical which means adjustments based on the phrases expressing it.” Certainly, the which means adjustments, and never solely in poetry: Pascal speaks right here of prose. The second fragment continues: “Meanings are given dignity by phrases as an alternative of conferring it upon them.” I do know no higher system for suggesting the inseparability of phrases and meanings. And if it can be crucial to not depart from a biblical textual content written in prose, all of the extra so ought to we stay as shut as attainable to a biblical poem, realizing that poetry, which doesn’t allow paraphrase, additionally doesn’t convey propositions—or it conveys them in a context that provides them their specificity. It appears to me that we wouldn’t have to attract doctrines from the Bible aside from people who the biblical writers themselves discovered there, for we can not contact backside in these deep waters; the world that’s revealed to us fully exceeds us. We are able to perceive solely what God reveals to us. The intelligence that he has given us permits us to replicate on what we learn, however any try and go additional—above all, systematic theology, whether or not it leads to the Summa Theologiae of Thomas Aquinas or the Institutes of the Christian Faith of Calvin—appears an error.

To imagine within the Bible—or, quite, to imagine the Bible, and to permit oneself to be satisfied that it’s the phrase of God, in no matter method one considers it—is to imagine what it says, with a supernatural religion that resembles, at an infinite distance, the boldness with which we learn a poem, accepting that its actuality is present in it and never in our exegeses. This permits for adhering to the reality that’s directly included within the phrases and liberated by them, regardless of the issue posed by the Flood, for instance, or the Tower of Babel. We don’t essentially know the precise nature of the reality that’s revealed to us, however we all know the place to search for it, simply as we don’t essentially perceive a poem however we search for the reply to our questions within the poem itself, with out including or subtracting something.

Poetry attracts our consideration to language and to the thriller of phrases, to their capability to create, nearly by themselves, networks of which means, surprising feelings, rhythms and a music for the ear and for the mouth that spreads by way of the whole physique and all one’s being. It acts equally on the world, by discovering, for the presences of the true, new names, and associations of phrases, of cadences, of sounds, that give to essentially the most acquainted beings and objects a sure strangeness that’s each disturbing and joyous. It burns up appearances, it uncovers the invisible, it opens, like a little bit casement or an important window, onto the unknown, onto one thing else. The shade of bushes that invitations us within the midst of sturdy warmth is transfigured when Racine’s Phèdre cries:

Dieux! que ne suis-je assise à l’ombre des forêts!

(Gods! why am I not seated within the shade of forests!)

Motive or good sense may object that one can’t be seated within the shade “of forests,” however solely within the shade of a tree, or, if one footage it within the thoughts, within the shade of a forest, within the singular. These plural forests represent a world seen anew, recreated by the creativeness, a world of nice magnificence that’s nearly cerebral, however that on the identical time on no account loses contact with actuality. We’re attracted by the grave sonority of “ombre,” which contrasts with the i sounds that precede it: “que ne suis-je assis …” The coolness of this shade, underneath forests which have develop into defending and enveloping, creates for Phèdre an eminently fascinating place, apt to save lots of her from her burning unavowable love for Hippolyte and from the horrible gaze of the gods. The helpful shadow trembles with a devastating ardour; the imagined place is crammed with human guilt.

The “which means” of the well-known verse is determined by the creativeness that inhabits it, and on the emotion that animates it, which might not be absolutely current with out its grammar and with out the sounds that it makes. The forests, actual, surreal, and resonating with the character’s need, disgrace, and aspiration, characterize, in a sudden imaginative and prescient, the true world: beloved, misplaced, attainable. And I don’t exclude the chance that these “forêts” are imposed on Racine by the need of rhyming them with “apprêts” on the finish of the previous line, and by the impossibility of writing the 4 syllables “de la forêt.” The arrival of poetry for a prosaic cause is under no circumstances surprising: important phrases and concepts regularly arrive in an indirect method.

As Henri Brémond writes, poetry produces in us “a sense of presence.” The world is there, not underneath its typical guise however in a language that alone may give it immediacy. The poetic act attracts near the true and, as a way to go to the depth of issues, it recreates them for us by welcoming them in sounds, rhythms, and limitless ramifications of meanings, and locations these recreations within the area of the attainable. In its personal method, and with out in any respect being supernatural, poetry too is a revelation. The Bible as revelation and as poetic speech provides equally and above all onto one thing else. Clearly, it doesn’t develop solely in poems, however its writings usually flip into verse, as if it tended towards poetry by supposing poetry to be the speech most applicable to the strangeness, to the transcendence of what it manifests. And allow us to suppose once more of the phrases of Jesus. He speaks very often in parables, as a way to current complicated truths within the type of tales and inside the life of some characters, and as a way to provoke his listeners—and us, his readers—to look, every time, for which means within the a number of aspects of a fiction. His affirmations in prose are equally poetic in that they don’t seem to be understood straight away; they ask that we obtain them as we obtain poetry, by turning into acutely aware of the thriller that accompanies them. For instance, in listening to “The dominion of heaven may be very close to,” or “That is my physique,” or “I’m the reality,” we really feel, I imagine, that they’re one thing aside from propositions, and we acknowledge behind these quite simple phrases a kind of hinterland of which means that we should discover as one explores the depths of a poem.

“I’m the reality” escapes from all of the modes of considering in Western philosophy.

Jesus, who’s the Phrase, speaks, certainly, and doesn’t write. All the things he says follows from a selected scenario, from a lived second. And so many books of the Bible started by being spoken, or had been destined, just like the Psalms, to be stated and sung, or they collect the phrases of an orator, like Ecclesiastes, or presuppose a dialogue, like Job or the Music of Songs. The Bible engages us continuously in listening, in turning into delicate to their methods of writing, to photographs that don’t clarify, and, ideally, to the music of thought. It’s true that almost all of us wouldn’t have entry to the unique texts, however wasn’t that foreseen? There are methods to grasp, even at a distance, how Hebrew and Greek perform, and it’s as much as us to hunt, in a easy translation—on the situation that it’s poetically devoted—the animation of the speech and the best way and the lifetime of the reality.

Studying the Bible is a “poetic” expertise. It affords us a theology in accordance solely to the etymological sense of the phrase: speech regarding God. For the Bible, which places us in entrance of one thing else, is itself different. Have we, in Europe, actually grasped the character of Christianity? Haven’t we as an alternative assimilated to our classes of thought and our habits of studying a faith that involves us from the Center East? Its Jewish origins on no account signify that Christianity lacks a common bearing, however they need to not be uncared for. God selected to disclose himself first by way of a those who had, century after century, their very own mind-set and writing, and the faith they transmitted bears the marks of this genesis. The Bible asks us to acknowledge the strangeness, the foreignness of Christianity, and to place in query our European method of approaching it. Recovering this Christianity that comes from elsewhere would change our studying of the Bible, and likely our method of proclaiming the Gospel.

Tailored from The Bible and Poetry by Michael Edwards, translated by Stephen E. Lewis. To be printed by New York Evaluate Books in August.

Michael Edwards is an Anglo-French poet and scholar. Born in Barnes, London, he’s the writer of twenty books and the primary English particular person ever to have been elected to the Collège de France and to the Académie Francaise.

Stephen E. Lewis is a professor of English on the Franciscan College of Steubenville and a translator of French literature.