Courtesy of Timmy Straw.

For our new collection Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve revealed in our pages. Timmy Straw’s “Brezhnev” seems in our Winter subject, no. 242.

How did this poem begin for you? Was it with a picture, an thought, a phrase?

There’s a scene I used to image rather a lot as a bit child within the eighties: two folks dancing slowly, intently, their our bodies seeming to know and anticipate one another—solely they’re additionally separated by a display, in order that neither has ever seen the opposite’s face. This was, I feel, a method I understood the world at the moment: this dance (so I imagined) is what shaped actuality itself—Reagan’s America, Gorbachev’s Soviet Union—and the dancers’ mutually blind place was like an engine, driving the world on. This made-up scene, and my grownup reminiscence of it, was definitely a significant goad to the poem. So was a bizarre little element: one in every of my older brothers might by no means perceive that my one-year-old self was not, actually, a young person like himself, and so would learn to me from The Annals of Imperial Rome and probably the most turgid highschool astronomy textbooks. Due to his mania for geopolitics, he additionally taught me tips on how to say “Brezhnev”—in order that, awkwardly, the Soviet normal secretary’s surname was one in every of my first phrases.

How did writing the primary draft really feel to you? Did it come simply, or was it tough to jot down? Are there laborious and simple poems?

“Brezhnev” was written in late lockdown, at a degree once I’d taken to swimming rather a lot—I had some vaguely science-y conviction that the massively elevated public-pool chlorine ranges could be incompatible with covid. I preferred to work out poems within the pool (in my head—no waterproof paper was concerned), and the primary draft of “Brezhnev” had one thing in it of the satisfying pull of a strong hour of the Australian crawl. It was spookily simple to jot down, perhaps as a result of it’s largely narrative, even a bit cinematic: the sense was much less of pursuing a brand new poem, with all its hidden legal guidelines and unusual hostilities, than of changing into more and more within the sequence of photographs showing in entrance of me. In actual fact, when the primary draft was carried out, studying it again felt a bit like a VHS movie on pause: the strain and blur of the vibrating picture.

However sure: there are undoubtedly poems which are fast to jot down and poems that may take years! I’m pondering of a poem (“The Thomas Salto”) that began in 2016 after which proceeded by way of most likely fifteen-plus insufficient iterations over six years earlier than arriving, final 12 months, at one thing I can dwell with. Poems start like migraines do, I feel, and also you eliminate them with comparable rigor—albeit not with aspirin, quiet, and a darkish room, however by writing and writing them down till they go away (hopefully into their completedness, most frequently into their failure!).

What have been you listening to / studying / watching when you have been penning this?

I used to be studying an essay by the Russian poet Olga Sedakova referred to as “Mediocrity as a Social Hazard.” In it, she quotes this luxuriously doomful line from Goethe, which I lifted: “You’re a disconsolate visitor on this darkish Earth.” Sedakova’s essay is audacious, lucid, problematic, and typically surly. (At one level she notes, by the use of an informal apart, that human will will be summarized as follows: “to ask for or refuse a drink, as on the cross.” To which I reply: Yikes! But additionally, minus the Christian referent: … perhaps.)

I used to be additionally listening to plenty of Bach (Varvara Myagkova’s recordings of the preludes and fugues) and to Future’s “Masks Off” (the remix, with Kendrick Lamar). I prefer to assume these songs had an impact on the poem’s kind on the web page, the way in which interstitial phrases like and or some are accented by way of the quickness and harshness of the road breaks—I used to be significantly desirous to get a number of the naked and virtually dingy fantastic thing about the counterpoint in Bach’s Fugue in E minor from E book 1, and the skittering play of the snare towards Kendrick Lamar’s verse on “Masks Off.”

What was the problem of this specific poem?

“Brezhnev” is expressly autobiographical, which isn’t a type of writing I typically do, and I discover it a bit scary—not for causes of “vulnerability” however as a result of such writing is embedded with the unimaginable crucial to “get it proper.” By “getting it proper” I imply being true to the dignity of the folks—on this case, my household—whom I’ve dragged into the poem, and who know very effectively the place and time and circumstances of which “Brezhnev” is a (smudged) mirror. If a poem is explicitly autobiographical, then by rights it exists not just for the sake of itself however for the precise, named folks in it—i.e., folks whom I like and who, whereas “within the poem,” are additionally at this very second on the market on earth, doing and pondering and feeling issues. All this made me nervous, and so, whereas the primary draft got here shortly, I fiddled with subsequent drafts for ages.

I additionally spent plenty of time checking out its kind—in writing “Brezhnev,” I had begun working on this new means, breaking the road based on a predetermined margin setting such that the emphasis lands, typically aggressively, on phrases that bear no which means in themselves (and, the). This skews the eye, I feel, towards operations and features within the poem and away from folks and issues (kind of like shining a highlight not on the actors and props however on, say, {the electrical} shops on the stage ground). I additionally needed the poem on the web page to invoke a cat’s cradle: the children’ recreation that thematizes, with nice simplicity, the notion that if you happen to tug on one factor, all the things strikes—a reasonably good abstract of Chilly Conflict geopolitics, and, I suppose, of our personal historic second.

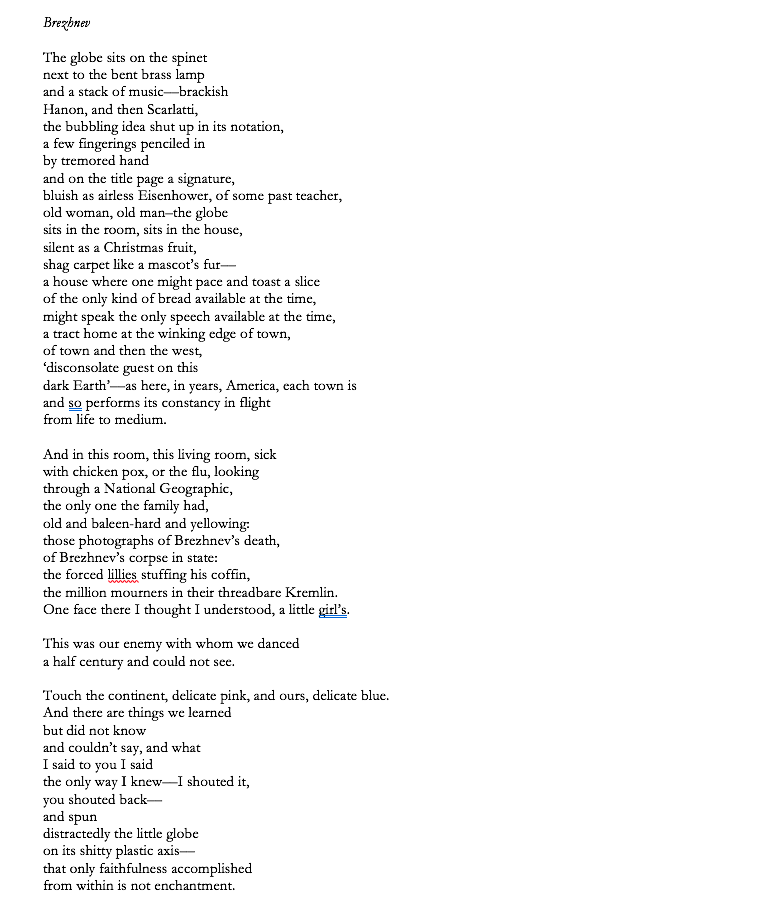

Do you may have pictures of various drafts of this poem?

I don’t normally hold drafts round, partly out of laziness and partly as a result of I don’t wish to look again and switch right into a pillar of salt; however I do have an early draft of “Brezhnev”: you’ll be able to see the three lengthy stanzas, with a couplet overdramatically wedged in there towards the top, plus some pointless exposition, the primary little bit of which I had the wherewithal to take away. The final bit (the ultimate six traces), nevertheless, I stored, till Chicu [Srikanth Reddy, the Review’s poetry editor] correctly advised I redact it. I had needed a denouement, some pleasing show of concluding reality (no matter that’s); however he noticed one thing way more attention-grabbing—the torque achieved in its refusal.

An early draft of “Brezhnev.”