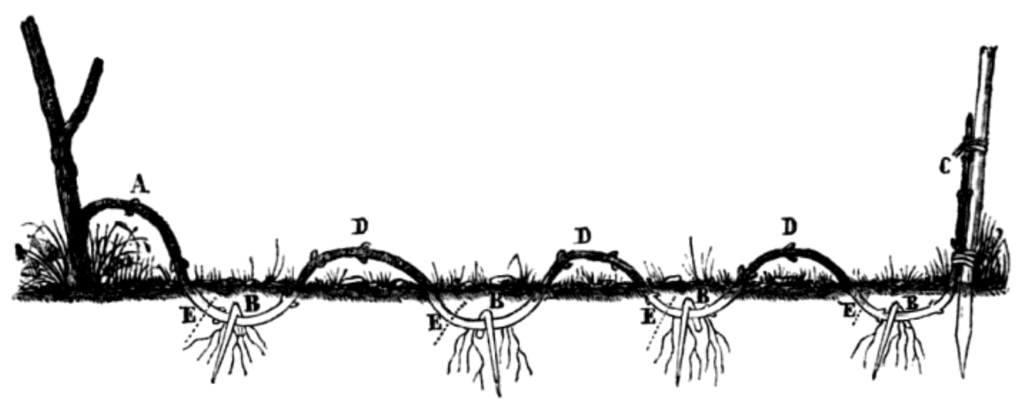

Alphonse du Breuil, Marcottage en serpenteaux, 1846. Public area, through Wikimedia Commons.

Just lately, I learn Virginia Woolf’s first printed novel, The Voyage Out, for the primary time. There, I made a discovery: it incorporates a character named Clarissa Dalloway. This encounter initially provoked delight, shock mixed with double take, like bumping into somebody I assumed I knew properly in a setting I by no means anticipated to seek out them, inflicting a quick mutual repositioning, bodily, imaginatively. (Ah! So we’re each right here? However in the event you’re right here, the place am I?) Then my emotions went unusual. For some motive, I felt disgruntled, nearly caught out: as if the world had been withholding one thing essential from me. How was I solely simply now catching up on what—for therefore many readers—have to be outdated information? Sure, there’s a Clarissa Dalloway in The Voyage Out. She’s married to Mr. Richard Dalloway: the couple have been stranded in Lisbon; they board the boat and the novel in chapter 3. She is a “tall, slight lady” with a behavior of holding her head barely to at least one aspect.

I used to be impressed by the boldness of this transfer: for Woolf to provoke a personality in a minor function after which, years later, to return to her, to open out a complete novel from her non-public intentions and on this approach proceed her (Mrs. Dalloway was printed a decade later, in 1925). It made me consider E. M. Forster’s two lectures on “character,” printed in Elements of the Novel in 1927. The primary is titled “Individuals.” The second: “Individuals (continued).” Then I remembered why I’d had that “caught out,” “I ought to have identified this” feeling: this identical strategy of novel-growth was additionally of nice curiosity to Roland Barthes. In his lecture programs on the Collège de France within the late seventies, he named it marcottage.

It’s a horticultural time period. A strategy of plant propagation, working as an illustration with bushes or bushes. It includes bending one of many plant’s increased, versatile branches into the bottom and fastening it there, a branch-part underneath the soil, to provide it the time and power to root. It was additionally, for Barthes, a technique of novel composition, one practiced by Balzac, by Proust. In an article (translated in 2015 by Chris Turner) on the discoveries that initiated Proust’s writing In Search of Misplaced Time, Barthes outlined the strategy as that “mode of composition by ‘enjambment,’ whereby an insignificant element given initially of the novel reappears on the finish, as if it had grown, germinated, and blossomed.” The element might be an object, a musical phrase, or the primary point out of a personality: the purpose is that it recurs, showing once more in a later quantity, connecting a number of books of a life’s challenge—solely that, every time, it’s allotted a distinct quantity of consideration, supplied with kind of house to develop (to develop). Marcottage. The plant instance Barthes reached for as an example this in his lectures was the strawberry plant. Strawberries do it spontaneously, “asexually,” sending out lengthy stems referred to as runners from the “foremost,” or “mom,” plant. The runner touches the soil a small distance away, takes root there, and produces a brand new “daughter” plant. Collectively, the vegetation type a pair, ultimately a community of mature vegetation, making it laborious to tell apart daughters from moms. The generative paths run backward in addition to ahead.

Marcottage might be a doable metaphor for translation. This work of frightening what vegetation, and maybe additionally books, already know the right way to do, what in reality they most deeply need to do: actively creating the situations for a brand new plant to root at far from the unique, and there stay individually: a “daughter-work” sturdy sufficient in its new context to throw out runners of its personal, in sudden instructions, inflicting the community of interrelations to develop and complexify.

For me, marcottage is a option to make sense of my very own translations of Barthes’s lecture programs. Formally, there have been two—two translations into English of two volumes of lecture notes printed in French greater than a decade in the past: The Preparation of the Novel and The right way to Stay Collectively. However to my thoughts, there have actually been 4: two additional books, translations in a extra expanded sense. This Little Artwork, my lengthy essay that stays near Barthes’s late work, steadily citing it, renarrating it, making an adjoining house to maintain considering with it. And now my novel The Lengthy Kind, a e-book that borrows its title from The Preparation of the Novel and shares many preoccupations with The right way to Stay Collectively: how, concretely, to stay collectively; the right way to proceed a relation with one other particular person; the right way to proceed a personality and a prose work, to maintain all of them going on the ranges of creativeness, rhythm, lodging, and composition; and the way these totally different orders of query might be made to speak with one another and proven to truly relate.

Another way, The Lengthy Kind can be related to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, if solely within the distant sense that it’s a novel that likewise unfolds over a single day. After which there may be this skinny, lately found line of attachment to The Voyage Out: when in Lisbon, the primary Mrs. Dalloway visits Henry Fielding’s grave. She pictures it. There, she additionally “let[s] free a small chook.” Jane Wheare, the editor of my Penguin version, appends a notice to this: “Henry Fielding (1707–54), the novelist, visited Portugal within the hope of regaining his well being, however died at Lisbon. Woolf herself loosed a caged chook at Fielding’s grave on 8 April 1905.” A element from life recurring in fiction (or, within the sequence of my very own studying, a element from fiction recurring in life), which sends me ahead or again to The Lengthy Kind’s closest relative: Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. A real “mom plant” within the sense that its compound construction, alternating “essay elements” with “fiction elements”, offered a template for my very own.

Whereas engaged on The Lengthy Kind, I got here throughout an extra reference to marcottage—this spontaneous technique of vegetation introduced as a possible writing method. It’s in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus and they’re citing another person: Carlos Castaneda. His passage is written as a set of directions. In Brian Massumi’s translation, it reads like this:

Go first to your outdated plant and watch rigorously the watercourse made by the rain. By now the rain should have carried the seeds distant. Watch the crevices made by the runoff, and from them decide the course of the circulation. Then discover the plant that’s rising on the farthest level out of your plant. All of the satan’s weed vegetation which might be rising in between are yours.

I acquired these directions as if they had been written for me. In my thoughts’s eye, I noticed the outdated plant, the primary, mom plant. I referred to as it the morning: the beginning of an imagined day. (I regarded up “satan’s weed,” or Datura stramonium, and discovered that’s an “invasive” plant of the nightshade household that has “steadily been employed in conventional drugs.” It additionally has hallucinogenic properties, “inflicting intense, sacred or occult visions.”) I then situated the plant rising on the farthest doable level away from the supply: to my thoughts, this was the night, bedtime. I knew I wished the novel to get there. So: I had this expanse between two factors, this marked-out length. However what in regards to the in-between? What may occur, what would develop, what might be grown out of that lengthy, slender channel? And who decides? Me? Sure, the directions gave the impression to be saying: It’s all yours. Between right here and there—all of it, something that falls in or shoots up, is yours. But in addition, not yours. For a way may it’s? The road is energizing for exactly the explanation that it makes this daring, untenable declare on what it’s not doable for anybody to completely personal: this unruly, self-directed, undirected progress. All these sudden interplants seeded by somebody or one thing else—assisted by pathways lengthy furrowed by different forces and the collaborative work of the rain. In a notice to her introduction to The Voyage Out, Wheare writes: “Woolf shared Henry James’s view {that a} novel ‘is extra true to its character in proportion because it strains or tends to burst, with a latent extravagance, its mould.’ ” On my avenue, a neighbor has positioned a line of strawberry vegetation on her sunny step. Every plant is contained inside its personal small, plastic, mainly impenetrable pot. Every plant is already overhanging its edges, throwing out shoots, reaching into the opposite’s earth.