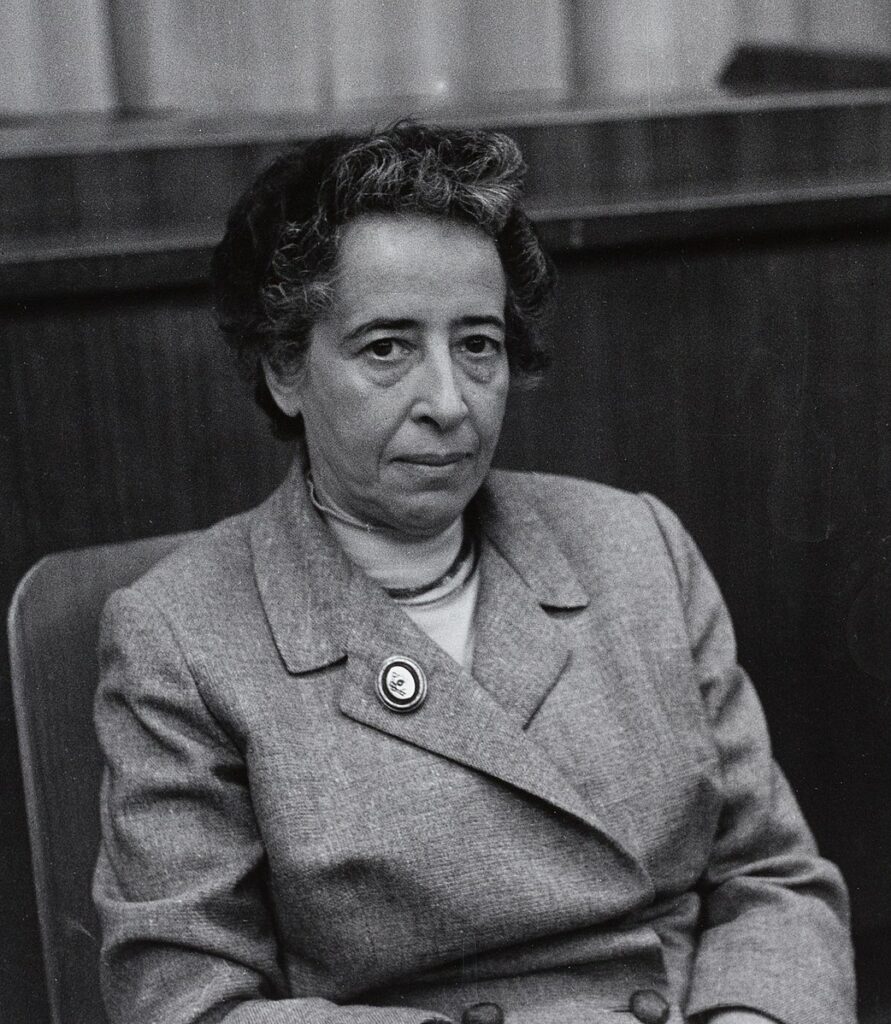

Hannah Arendt, 1958. {Photograph} by Barbara Niggl Radloff. Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie. Licensed underneath CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

For some time there within the late nineties, it appeared to me like each different ebook of poetry that I flipped open within the bookstore was prefaced by an austere epigraph from the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Wittgenstein—for all their many variations—get pleasure from a particular standing as “poets’ philosophers” within the annals of literary historical past. Different lofty thinkers fly underneath poets’ collective radar; I’ve but to come back throughout a quantity of verse prefaced by a citation from David Hume. What makes some philosophers, and never others, into poets’ philosophers stays a thriller to me. However I’ve by no means actually considered Hannah Arendt as one in every of them.

Unemotional, anti-Romantic, and doggedly insistent on expunging unruly emotions from collective life, Arendt could appear to own the least lyrical of temperaments, however a brand new quantity of her poetry reveals that the creator of sobering works like The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Situation was writing ardent and intimate verse in her off-hours. We’re happy to function Samantha Rose Hill’s new translation, with Genese Grill, of an untitled poem from Arendt’s manuscripts in our Fall 2024 challenge.

Now housed in Arendt’s archive on the Library of Congress, the poem is dated to September 1947, six years after the thinker’s arrival in the USA. Although she had by then settled on New York’s Higher West Aspect, Arendt displays upon what she’d left behind on her life’s journey on this wistful poem:

This was the farewell:

Many buddies got here with us

And whoever didn’t come was now not a buddy.

The bracing conclusion of Arendt’s opening stanza lands with the impression of a sensible realist’s rebuke to a sentimental idiot: Friendship is companionship; due to this fact, whoever will not be a companion can’t be thought of a buddy. (There’s one thing syllogistic to the thinker’s adoption of tercets for this poem’s type.) In her introduction to What Stays: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt, which will likely be printed later in December, Hill chronicles how Arendt’s pocket book of poems accompanied her via a succession of farewells: when she fled Germany after her launch from the Gestapo jail in Alexanderplatz within the spring of 1933; when she left her second life in Paris to report back to the internment camp at Gurs seven years later; and when she escaped on foot and by bicycle to Lisbon, the place she boarded the SS Guinee for Ellis Island on Might 22, 1941. “This was the prepare: / Measuring the nation in flight,” Arendt writes, “and slowing because it handed via many cities.”

From its melancholy opening to its bemused conclusion, Arendt’s poem displays the emotional passage of many who depart residence to take up residence in a international land. It begins as an aubade, or music of parting, and it ends with the enigma of arrival:

That is the arrival:

Bread is now not referred to as bread

and wine in a international language adjustments the dialog.

For the German speaker newly arrived in America, bread is now not Brot. One irony of Arendt’s historic displacements lies in how her unique German phrase for bread is now effaced by “bread” within the English translation. An extra irony is to be discovered within the poem’s ultimate line, the place “a international language” intrudes on what would in any other case learn: “and wine adjustments the dialog.” The important goal of wine—at a cocktail party, as an example—is to vary the dialog. However what’s wine in a international language? When lots of your dinner friends are, such as you, serial émigrés who’ve fled Europe within the political wake of World Warfare II, wine serves a further goal; anybody who’s discovered themselves just a little extra tipsily fluent at a cocktail party overseas will perceive how “wine in a international language adjustments the dialog.” Arendt made a house away from residence for herself—and for others—in New York at 317 West Ninety-Fifth Road and, later, at 370 Riverside Drive, the place she entertained fellow expatriates like Hermann Broch, Lotte Kohler, Helen and Kurt Wolff, Paul Tillich, and Hans Morgenthau. The marginally slanted rhyme of “Stadt” with “Gespräch” that concludes the poem in Arendt’s unique German hyperlinks the creator’s mid-century Manhattan to the bonhomie of mental trade; “metropolis” sounds just a little like “dialog” within the poet’s mom tongue.

Arendt’s poem, then, tells the story of her farewell to Europe and her arrival in the USA in a dozen traces of verse. Nevertheless it’s additionally a self-aware murals that quietly asserts its personal place within the German poetic custom—the bread and wine invoke the literary sacraments of Friedrich Hölderlin’s celebrated poem “Brod und Wein.” (“Bread is the fruit of the earth, but it’s blessed additionally by gentle,” writes Hölderlin. “The pleasure of wine comes from the thundering god.”) German poetry, for Arendt, was a continuing presence in each coronary heart and thoughts. “I do know a moderately massive a part of German poetry by coronary heart,” she stated in a 1964 interview on German nationwide tv. “The poems are all the time one way or the other at the back of my thoughts.” She wrote her first poems when she was an adolescent; a few of these early literary efforts had been addressed to her trainer—and lover—on the College of Marburg, Martin Heidegger. These early love poems remained secret, just like the affair that produced them, till after her demise. Studying them now, we will see the intimate affiliation of poetry and philosophy throughout this formative interval in Arendt’s life. But her poems, not like her philosophy, remained a personal affair for Arendt to the tip. We don’t know if she ever confirmed her poems to her shut buddies Robert Lowell, Randall Jarrell, and W. H. Auden in New York; to our information, solely her second husband, the poet and thinker Heinrich Blücher, learn her verse. The ultimate poem to be discovered within the Library of Congress archive is labeled “January 1961, Evanston.” Its creator was about to depart from a residency at Northwestern College to attend Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem. What she noticed there could have marked the tip of poetry for Hannah Arendt.

Srikanth Reddy is the poetry editor of The Paris Evaluation.